Fantasia 2017, Day 2: Tilting at Ghosts (Tilt, A Ghost Story, and Museum)

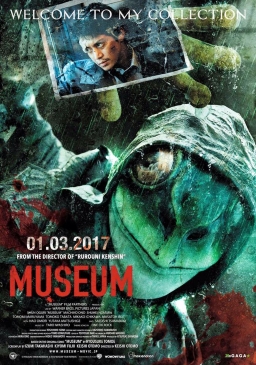

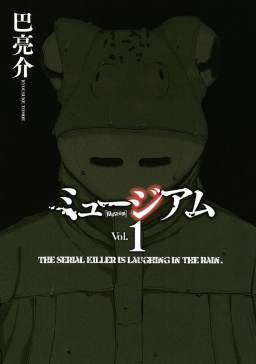

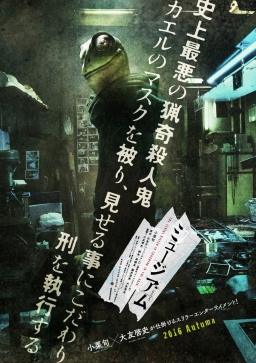

Friday, July 14, felt like my first real day at the 2017 Fantasia Festival. After only one film the night before, I had three movies I wanted to see that afternoon and evening. First would come Tilt at the 175-seat J.A de Sève Theatre, a thriller that was drawing attention on the festival circuit for its political subtext. After that, at the 700-seat Hall, would come A Ghost Story, a movie about loss; I thought it looked slightly more interesting than the comedic manga adaptation Teiichi: Battle of the Supreme High because A Ghost Story depicted its ghost in the form of an actor with a sheet over his head. The sheer brazenness was appealing. Besides, after that my last film of the day would be another manga adaptation at the Hall, Museum (Myûjiamu), directed by Keishi Otomo. I’d seen and enjoyed two other adaptations by Otomo before, the third Rurouni Kenshin film two years before and then last year The Top Secret: Murder in Mind. The odds seemed good for Museum, a crime thriller about a cop tracking down a frog-masked serial killer.

Friday, July 14, felt like my first real day at the 2017 Fantasia Festival. After only one film the night before, I had three movies I wanted to see that afternoon and evening. First would come Tilt at the 175-seat J.A de Sève Theatre, a thriller that was drawing attention on the festival circuit for its political subtext. After that, at the 700-seat Hall, would come A Ghost Story, a movie about loss; I thought it looked slightly more interesting than the comedic manga adaptation Teiichi: Battle of the Supreme High because A Ghost Story depicted its ghost in the form of an actor with a sheet over his head. The sheer brazenness was appealing. Besides, after that my last film of the day would be another manga adaptation at the Hall, Museum (Myûjiamu), directed by Keishi Otomo. I’d seen and enjoyed two other adaptations by Otomo before, the third Rurouni Kenshin film two years before and then last year The Top Secret: Murder in Mind. The odds seemed good for Museum, a crime thriller about a cop tracking down a frog-masked serial killer.

But the day opened with Tilt. Directed by Kasra Farahani from a script he wrote with Jason O’Leary, it follows a documentary filmmaker, Joe (Joseph Cross), whose wife Joanne (Alexia Rasmussen) is pregnant. Joanne’s making some money as she trains to become a nurse, but Joe’s having problems putting together his second film, about the economy and the myth of an American “golden age.” Over the course of Tilt — the title, we’re told, of Joe’s well-received first documentary, about control and chaos in pinball — we see Joe slowly lose his grip on reality as he strains to get his film’s material into some kind of shape. He takes to walking aimlessly around nighttime Los Angeles, his sanity deteriorating. Will he find help before he reaches a breaking point?

The movie’s already drawn some attention because contrasting with Joe’s increasingly ragged work on his film, with his rants about the 1950s and American empire, is the concurrent rise in the background of Donald Trump as glimpsed through news reports and the characters’ disbelieving jokes. Given the lead time involved in film production, there’s yet to be a substantial cinematic response to Trump’s election, so the Trumpian motif in Tilt stands out. Still, it’s mainly an element in the film’s atmosphere: media reports, snide jokes, a jump scare involving a Trump mask that I suppose we must consider cinema’s first Trump scare. It weighs heavily only perhaps because of this particular historical moment, and because we’ve not yet gotten to the point of frequently seeing Trump in fiction films. But, as Farahani has pointed out in interviews, Trump’s in the movie only because he seemed to the filmmakers to represent some of the themes they were working with — a kind of white male entitlement and anger. Tilt isn’t a response to the America Trump is making, so much as a look at the emotional texture Trump has seized upon.

If Trump is a kind of impressionistic flourish, then, the movie must rely on its dramatic structure to build its themes and texture, developing them in such a way that the Trumpian references make logical sense in extending its ideas. And here I felt there were real problems. The plot unfolds coherently in the sense of building inevitably to the film’s climax, but much of Joe’s descent felt to me unmotivated. I didn’t get a sense of what was causing him to fall apart. There’s a kind of over-inevitability that settles in to the film, as though we’re watching less a tragedy and more a series of moments in a case study: a straight line and not a narrative arc.

If Trump is a kind of impressionistic flourish, then, the movie must rely on its dramatic structure to build its themes and texture, developing them in such a way that the Trumpian references make logical sense in extending its ideas. And here I felt there were real problems. The plot unfolds coherently in the sense of building inevitably to the film’s climax, but much of Joe’s descent felt to me unmotivated. I didn’t get a sense of what was causing him to fall apart. There’s a kind of over-inevitability that settles in to the film, as though we’re watching less a tragedy and more a series of moments in a case study: a straight line and not a narrative arc.

Certain story choices feel particularly odd. Joe takes some mushrooms near the end of the film, which may or may not be actual hallucinogens. That’s unnecessary: Joe’s already far gone, and if the point is that he’s seeking out his own destruction, there strike me as being better ways to establish that. Conversely, a travel book glimpsed in the last moments of the film suggests he’s planning to get away from what remains of his life — but we’ve seen him reading the book much earlier, suggesting a longer period of premeditation. Finally, there’s a point where Joe tries to talk to his wife about his mental problems; she deflects his concerns, suggesting he take up a new job. It’s unconvincing because the phrases Joe uses strike me as language someone training to be a health-care professional would almost have to view as a red flag. Which, in this case, does not happen.

Most crucially, we soon come to realise that Joe was involved in some kind of incident before the movie opens: the film begins with Joe and Joanne returning from a vacation in Hawaii, and we soon learn that while in Hawaii Joe had some kind of encounter that sets up his descent into madness. The problem is that we never really know exactly what happened in Hawaii, why Joe did whatever exactly he did, or even how much he was at fault. The film starts too late, and never gives us enough puzzle pieces to fill in the missing backstory.

Most crucially, we soon come to realise that Joe was involved in some kind of incident before the movie opens: the film begins with Joe and Joanne returning from a vacation in Hawaii, and we soon learn that while in Hawaii Joe had some kind of encounter that sets up his descent into madness. The problem is that we never really know exactly what happened in Hawaii, why Joe did whatever exactly he did, or even how much he was at fault. The film starts too late, and never gives us enough puzzle pieces to fill in the missing backstory.

The acting doesn’t go far enough to make up for the lack of character in the script. Rasmussen’s solid enough, but the film has to be carried by Cross, and his Joe is too much of a blank. He’s able to play what a scene requires, but isn’t able to make up for the gaps in the script where character development should have been. It’s a competent acting job, but not good enough to build from the text to create the sense of a character arc. Add to that some moments of odd staging, notably a kind of physical confrontation above a cliff that feels improbable on a basic kinesthetic level, and the result is a disjointed sense through much of the film.

There’s a lack of weight to the story. Farahani’s said that he and O’Leary are “not horror people,” and you feel that in the construction of the film; the plot’s rudimentary, foreshadowing’s too heavy, ominous music is unearned. A dream sequence with a heavy-handed reference to crossing the Styx (presumably entering the underworld) builds neither tension nor any sense of unreality. The lack of drama begets a lack of tension, undercutting any horrific feel notwithstanding some atmospheric photography.

There’s a lack of weight to the story. Farahani’s said that he and O’Leary are “not horror people,” and you feel that in the construction of the film; the plot’s rudimentary, foreshadowing’s too heavy, ominous music is unearned. A dream sequence with a heavy-handed reference to crossing the Styx (presumably entering the underworld) builds neither tension nor any sense of unreality. The lack of drama begets a lack of tension, undercutting any horrific feel notwithstanding some atmospheric photography.

That photography provides the movie with many of its stronger moments. Joe’s nighttime walks around Los Angeles have a solid sense of atmosphere and of emptiness, less like noir and more like the experiences of a nightwalking flâneur. A crowded scene celebrating the Day of the Dead is almost unearthly. And yet the effect of these things on Joe isn’t brought out. One has to read the film backward, focussing on the themes implied by Trump: Joe’s fear of other cultures, and of non-white people, and therefore how he reacts to what he finds as he walks about. The problem is that these things are perhaps the least interesting element of the nighttime scenes, which seem to hint at some more profound kind of psychogeographical subtext. The more obvious themes, on the other hand, give small moments throughout the film excess weight, as when you look back in your memory at someone you once trusted and later found didn’t deserve that trust: you realise there were all kinds of small hints and signs pointing to who they were, trivial at the time but clear in retrospect. So here, if you know the subtext and the themes of the film then Joe’s early grumbling at a Spanish-language robocall has some obvious meaning. But it lacks any dramatic relevance, any point narratively, and so it feels overdetermined — one of a series of points that are too on-the-nose.

One might expect Joe’s documentary would make an interesting film-within-the-film, but I couldn’t find a meaningful contrast with Joe’s own life. It wasn’t even clear to me how good the documentary was supposed to be; Joe’s narration seemed loose and over-general. But then it’s also not clear to me why Joe’s hit a creator’s block. As an artist his viewpoint is unclear and his sensibility rudimentary, the least visual filmmaker I’ve ever seen on film. Politically, he’s anti-Trump, but the film doesn’t really examine the tension between his conscious ideals and his unconscious nostalgia for an imagined America that would recognise his worth.

One might expect Joe’s documentary would make an interesting film-within-the-film, but I couldn’t find a meaningful contrast with Joe’s own life. It wasn’t even clear to me how good the documentary was supposed to be; Joe’s narration seemed loose and over-general. But then it’s also not clear to me why Joe’s hit a creator’s block. As an artist his viewpoint is unclear and his sensibility rudimentary, the least visual filmmaker I’ve ever seen on film. Politically, he’s anti-Trump, but the film doesn’t really examine the tension between his conscious ideals and his unconscious nostalgia for an imagined America that would recognise his worth.

That’s politics again; but it strikes me that this is less a Trump horror movie than a kind of Trumpsploitation film, a movie that draws attention for its use of Trump and the themes associated with Trump while the plot has little to do with any of these things. The movie’s sense of politics is very general, if not confused. The handling of class struck me as especially odd: although the characters are nominally struggling financially, they vacation in Hawaii and own a house in Los Angeles (a very small house, but a house). It may of course be that I’m missing things; as a Canadian I have no sense of a golden age in the 1950s, which the movie implies is linked to Trump’s popularity. There are Trump supporters in Canada — a few months ago someone told me they met one — but not many. I’m not living in Trump’s America, and I don’t know if I’m missing some set of cultural cues that would make the movie’s themes cohere. As it is, I can say only that Tilt didn’t work for me as a drama.

From Tilt I had a few minutes before going across the street, from Concordia University’s McConnell Building to the unremarkable tower of the Hall Building, home to the Hall Theatre (officially the Sir George Williams University Alumni Auditorium, in honour of one of the two universities whose merger created Concordia). With the 400-seat D.B. Clarke Theatre downstairs in the Hall Building, Fantasia has its three main theatres literally within seconds of each other. This year they also had a media lounge in the McConnell Building complete with beanbag chairs, a surprisingly relaxing setting for resting between films and talking about movies. I will note here that I’ve learned a lot about film from the other critics I’ve met at Fantasia, among them Sandro Forte of Cinetalk.net, Giles Edwards of 366weirdmovies.com, and Thomas O’Connor of Goombastomp.com; and among the things I’ve learned is how much the experience of watching a movie gains if you can talk about it afterward with smart, knowledgeable people.

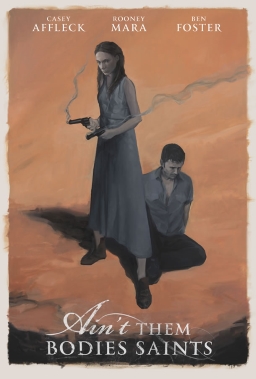

The next movie experience on my agenda was A Ghost Story, which was introduced by writer/director David Lowery as “the least scary movie you will see at this entire festival.” He may have been right, but that’s fine; a ghost story, after all, is not necessarily a horror story. In fact, Lowery, director of Disney’s 2016 version of Pete’s Dragon, has here crafted a meditation on loss and time. It begins with a couple, never named — credits refer to them only as C (Casey Affleck) and R (Rooney Mara; both Affleck and Mara had been in Lowery’s 2013 film Ain’t Them Bodies Saints). They’re contemplating leaving their house. Then C dies in a car accident. He rises as a ghost, and stands around the house, a sheet over his head, observing R as she mourns, as time passes, as, eventually, doing little himself, he circles around to a kind of second chance.

The next movie experience on my agenda was A Ghost Story, which was introduced by writer/director David Lowery as “the least scary movie you will see at this entire festival.” He may have been right, but that’s fine; a ghost story, after all, is not necessarily a horror story. In fact, Lowery, director of Disney’s 2016 version of Pete’s Dragon, has here crafted a meditation on loss and time. It begins with a couple, never named — credits refer to them only as C (Casey Affleck) and R (Rooney Mara; both Affleck and Mara had been in Lowery’s 2013 film Ain’t Them Bodies Saints). They’re contemplating leaving their house. Then C dies in a car accident. He rises as a ghost, and stands around the house, a sheet over his head, observing R as she mourns, as time passes, as, eventually, doing little himself, he circles around to a kind of second chance.

The movie’s filmed in a squarish aspect ratio, with rounded corners like an old silent film. It fits. This is not a film structured around brilliant dialogue, though what’s there works, and there’s an extended monologue near the centre of the movie about universal death that gives the film’s themes some focus. The ghost of C is silent, only once throwing a tantrum when another family moves into his house and even then making no sound himself, only breaking dishes and terrifying the living. The movie’s a primarily visual experience, built around long takes, around stillness, around the oddly evocative image of a ghost as a sheet with eyes. More accurate to say it like that than to say a man with a sheet over his head: the ghost’s a sheeted mass, as though it’s what remains when the flesh has been erased, worn away by time and death.

The ghost is partially a human construct, but ghosts in this movie haunt houses — and what’s a house but a thing made by human hands? The ghosts of our houses are part of what they are, as much as the houses are a part of a community of urban space. R tells C early on that when she was younger and her family moved frequently she would leave messages hidden in the houses she left; she will do so here, and that gives a semblance of dramatic tension to the film, giving the ghost of C a goal on which to obsess — but perhaps R leaving these pieces of herself in the spaces she once inhabited is also another way of exploring the connection between place and spirit. C ultimately will live through the entire existence of the house as a place for people, the point when a shelter was first established on that patch of land to the point where communal life ends; time works differently for ghosts, it would seem.

The idea of playing a ghost as an actor with a bedsheet sounds like it ought to be self-aware, but if there’s irony here it’s nothing to do with cynicism. There are playful references — early on a character reads Virginia Woolf’s short story “A Haunted House,” later we see modernist and post-modernist love stories like Love in the Time of Cholera and A Farewell to Arms on R’s shelf. The Woolf story is featured particularly prominently; tonally it’s an apt choice, another story of love and death, told in an unconventional style, mixing times. There’s a precision to the film that recalls Woolf as well, a mastery of material and form.

The idea of playing a ghost as an actor with a bedsheet sounds like it ought to be self-aware, but if there’s irony here it’s nothing to do with cynicism. There are playful references — early on a character reads Virginia Woolf’s short story “A Haunted House,” later we see modernist and post-modernist love stories like Love in the Time of Cholera and A Farewell to Arms on R’s shelf. The Woolf story is featured particularly prominently; tonally it’s an apt choice, another story of love and death, told in an unconventional style, mixing times. There’s a precision to the film that recalls Woolf as well, a mastery of material and form.

Lowery takes considerable risks in this movie, and asks more of some viewers than they may be prepared to give. As I said, the movie’s built around long takes, and it’s often quite slow. There’s an already-notorious scene in which R eats a pie in two shots that together last several minutes. That doesn’t sound long, but it’s an eternity in film time. You start to become aware of yourself sitting in a chair in a theatre, watching a woman grimly dig into a pie. And then you move past that, to empathise with the grief behind her determination, the emotion driving her to stab a fork into the pie again and again. As all the while, unknown to her C’s ghost watches. And, finally, there is a payoff and the shot ends with an almost physical shock to the senses.

Not everyone wants that sort of an experience, especially if they go into a film thinking it’s a horror story. It is important to know roughly what sort of story you will see, with what sort of ambition. Technically, the film is precise in lighting and texture and, yes, pacing. I think Lowery did what he wanted to do, and it works. At 92 minutes including credits, I think the length is just right. There’s a temptation to say it’s too long, that it might have worked as a short, but I don’t know how it’d be possible to edit it down without radically transforming the whole experience of the movie.

There is a fable-like feel to the film, but also, it must be said, a poetic sense. In the way that a spare line of poetry leaves unspoken much of what it means and inspires deep reflection, shots in A Ghost Story imply more than they say and by prolonging themselves come to mean yet more again. Lowery has an eye for moments, here; an early scene in which R and C fall asleep together feels real and touching in a way I’ve rarely seen in a film. The sudden transition to the tragedy afterward is stark: here is love and death, soon followed by love in death. Because these things are believable, the story is believable without any need for exposition or prosaic worldbuilding.

There is a fable-like feel to the film, but also, it must be said, a poetic sense. In the way that a spare line of poetry leaves unspoken much of what it means and inspires deep reflection, shots in A Ghost Story imply more than they say and by prolonging themselves come to mean yet more again. Lowery has an eye for moments, here; an early scene in which R and C fall asleep together feels real and touching in a way I’ve rarely seen in a film. The sudden transition to the tragedy afterward is stark: here is love and death, soon followed by love in death. Because these things are believable, the story is believable without any need for exposition or prosaic worldbuilding.

In a movie that seems concerned with ideas of home and with cycles of time, there was one odd note. We see the next family to move in to C and R’s house after C dies, and they’re Spanish-speakers whose dialogue is left untranslated. Later, we see the first European settlers on the land that will become the site of the house, and they’re killed by the indigenous inhabitants. While that does cast a useful light on the whole history of the house — strengthening a theme about seeing things from different angles that emerges more fully in the rest of the film — it does in retrospect make the choice of a Hispanic family taking over the place from a WASP-appearing family seem politically fraught in a way I’m not sure was intended. (Of course, having seen Tilt just beforehand may have caused me to have these sorts of issues more prominently in mind than usual.) Still, the story of the house doesn’t end there, which is key. Yet more people come, as C’s ghost observes them, increasingly separate from the emotions of the physical world, increasingly dissociated from what it sees as time flickers by more and more quickly. Nothing ends, changes aren’t permanent, and in the end what we think of as space is shaped by time — and by human perception.

A Ghost Story is remarkable for its formal daring, and for its ability to get at powerful themes through strong and unconventional character-building. Not horrific, it is nevertheless deeply emotional. It captures a sense of eternity, and of the circular shape of time. It captures moments in which the human meets the inhuman, and in which the human becomes inhuman. It is about place, and community, and death, and love. It is about structure, the structures in which we live and the structures by which we tell stories and (for some) make movies. And yet it’s more than a formal exercise. It’s unconventional, ambitious, and involving. To me, it’s a great success.

A Ghost Story is remarkable for its formal daring, and for its ability to get at powerful themes through strong and unconventional character-building. Not horrific, it is nevertheless deeply emotional. It captures a sense of eternity, and of the circular shape of time. It captures moments in which the human meets the inhuman, and in which the human becomes inhuman. It is about place, and community, and death, and love. It is about structure, the structures in which we live and the structures by which we tell stories and (for some) make movies. And yet it’s more than a formal exercise. It’s unconventional, ambitious, and involving. To me, it’s a great success.

After the movie ended, Lowery came out for a question-and-answer period. According to my quickly-scribbled notes, Lowery was asked about the interest in Americana in his works and his sense of time periods. Lowery said this came in large part from learning and enjoying history when young, and that he also had an interest in folklore and folk traditions. His father sang folk music, and Lowery’s interest in his father’s music led him into folklore. Asked about the transition from making his previous film, Pete’s Dragon, to this one, Lowery observed that A Ghost Story was shot in 19 days while Pete took 80. Besides the difference in time, the budget for A Ghost Story was “one half of one day’s production” of Pete. Yet the experience was similar, as he was working with the same crew and equipment. He credited Disney for this, and for allowing him to make Pete a personal film.

Asked whether A Ghost Story flips genre narrative on its head, Lowery said that he didn’t see it — though he acknowledged that at one point it retold Poltergeist from the ghost’s perspective. He thought the movie was a way to address things in his own life, including his nostalgia, his attachment to the past, and his fear of the future. Asked if he thought the impact of the film would be the same without the image of the ghost in the bedsheet, he immediately said no, and stated that the look of the ghost was intrinsic to the movie — in fact preceding anything else. Lowery said that in his first film, at seven years old, he’d dressed his brother in a ghostly sheet; and that he liked the childishness of the image, the potential of emotion in it, and the way the humour of it fades as you watch the movie.

Asked why the characters had no names, Lowery answered that while he was writing he wanted to make the ghost more real on the page, and took the names of the living characters out to help him and others who read the script get the story in perspective; he ended up keeping that for the credits. Asked how much improvisation was in the long pie-eating take, Lowery said that the take was played as scripted. He knew it would be an important sequence, and it was shot as written without a preset running time. He as director and Rooney Mara as performer knew it was an important part of the film, and did it in one take. Lowery was then asked how he got emotion to appear on a faceless ghost, and he said that it was largely mechanical. He’d thought that an actor’s body language would be enough to convey emotion, even through a sheet, but found that didn’t work; the result felt less like a ghost than like an actor with a sheet over his head. He wanted something more surreal, and ended up having his actor increasingly still — as well as shooting him at a different frame rate. Lowery spoke about the ghost working like a character in a cartoon, a blank space into which the audience projects themselves, a blank that makes identification easier. It feels like the ghost’s face changes, but it’s always the same.

Asked why the characters had no names, Lowery answered that while he was writing he wanted to make the ghost more real on the page, and took the names of the living characters out to help him and others who read the script get the story in perspective; he ended up keeping that for the credits. Asked how much improvisation was in the long pie-eating take, Lowery said that the take was played as scripted. He knew it would be an important sequence, and it was shot as written without a preset running time. He as director and Rooney Mara as performer knew it was an important part of the film, and did it in one take. Lowery was then asked how he got emotion to appear on a faceless ghost, and he said that it was largely mechanical. He’d thought that an actor’s body language would be enough to convey emotion, even through a sheet, but found that didn’t work; the result felt less like a ghost than like an actor with a sheet over his head. He wanted something more surreal, and ended up having his actor increasingly still — as well as shooting him at a different frame rate. Lowery spoke about the ghost working like a character in a cartoon, a blank space into which the audience projects themselves, a blank that makes identification easier. It feels like the ghost’s face changes, but it’s always the same.

Asked why these actors, Lowery’s first answer was that he picked Casey Affleck on the basis of him being willing to come to Texas and let him put a sheet over his head. More seriously Lowery said that he wanted the couple onscreen to feel like a real couple and have chemistry, in order to make the sense of loss more strongly felt, and Affleck and Mara had experience together from Ain’t Them Bodies Saints. Lowery was then asked about the squarish aspect ratio of the film, whether it was selected for the retro appeal, or to create a sense of voyeurism, or whether he was a fan of Tarkovsky. Lowery said he was a fan of Tarkovsky, and of that aspect ratio. He felt it created a proscenium when seen on a modern TV, creating the voyeuristic sense. He also wanted to add to the sense of being trapped, which he felt the square did. He added the rounded corners in postproduction, a nostalgic touch in a film about letting go of nostalgia.

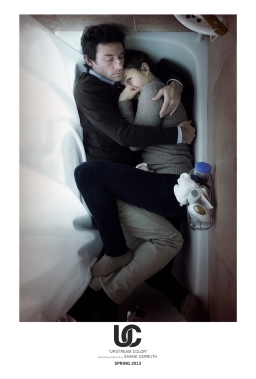

In answer to a question about his use of genre conventions, Lowery said that horror was his favourite genre and that Poltergeist was in his mind, as was The Conjuring, Part 2. The latter movie came out while he was shooting, and he loved it. Lowery said he has a whole history of horror movies in his head, and promised someday to make a true honest-to-goodness horror film. Asked about director Shane Carruth’s involvement in the film, Lowery said Carruth (director of Primer and Upstream Color) was a friend from Texas. Lowery had helped him edit Upstream Color, and Carruth helped edit A Ghost Story, and also suggested shots. Lowery said it was wonderful to have him as a friend and collaborator, even in a limited instance like this.

Lowery was asked if the address of the house in the film, shown prominently in several shots, was symbolic; he said it wasn’t, but that in editing they’d noticed it stood out and wondered what they could read into it. And yet in the end, they couldn’t find anything. Asked next if he was a cynic, Lowery said he’d started as one, and chose to change because he decided he didn’t want to be a nihilist. He wrote the monologue in the film about hope and the death of all things as a way of getting through his cynicism; he felt the character in the film gets two-thirds of the way through, but that the movie gets all the way through. Asked about the production design of the movie, Lowery said his production designer is a friend who works on all his movies, helping him figure out the story. The composer also works on all his films, and Lowery doesn’t have to talk to him now to explain what he wants; both understand him, while he knows what they bring to making movies. Texture, he said, is a big thing.

Lowery was asked if the address of the house in the film, shown prominently in several shots, was symbolic; he said it wasn’t, but that in editing they’d noticed it stood out and wondered what they could read into it. And yet in the end, they couldn’t find anything. Asked next if he was a cynic, Lowery said he’d started as one, and chose to change because he decided he didn’t want to be a nihilist. He wrote the monologue in the film about hope and the death of all things as a way of getting through his cynicism; he felt the character in the film gets two-thirds of the way through, but that the movie gets all the way through. Asked about the production design of the movie, Lowery said his production designer is a friend who works on all his movies, helping him figure out the story. The composer also works on all his films, and Lowery doesn’t have to talk to him now to explain what he wants; both understand him, while he knows what they bring to making movies. Texture, he said, is a big thing.

The last question was a two-parter. First, Lowery was asked about a song that plays in the film, ostensibly composed by Casey Affleck’s character. Lowery said the film’s composer, Daniel Hart, wrote it for his band’s album, and Lowery wrote it into the screenplay because he loved it so much. All the music in the film was based on some element of the song, so that the audience is being prepared to hear it when it’s finally played in full. Then he was asked why he didn’t use subtitles when the Spanish-speaking family moved into the house, and he said that he sometimes enjoys seeing a movie when he doesn’t understand what language it’s in. He himself reads Spanish, but doesn’t speak it. Since he knew the dialogue didn’t convey any plot points, he felt he could leave out subtitles, allowing an English-speaking audience to appreciate the dialogue musically.

The questions finished, the audience left the theatre and I got in line for the next film: Museum, director Keishi Otomo’s adaptation of Ryôsuke Tomoe’s manga of the same name. Otomo wrote the script with Kiyomi Fuji, his co-writer for the Rurouni Kenshin movies, and Izumi Takahashi, with whom he co-wrote his adaptation of The Top Secret: Murder in Mind. Museum’s closer to the latter than the former, neither fantasy nor science-fiction but a modern-day crime story about an everyman (if smarter-than-average) cop, Hisashi Sawamura (Shun Oguri, TerraFormars, and also at Fantasia this year in the live-action adaptation of Gintama), trying to track down a murdering genius (Satoshi Tsumabuki). But the closer he draws to the killer, who’s seen in public only in a frog mask, the clearer it becomes that Sawamura’s estranged wife (Machiko Ono, Too Young to Die!) is also a target.

The movie starts out with promise, introducing us to grisly crimes and hinting at the mysterious but deranged intelligence that planned them. Warning signs appear: there’s a tendency for things to happen too conveniently, as when Sawamura and his assistant Nishino (Shûhei Nomura) realise from circumstantial evidence that an apparent innocent onlooker is actually the killer. But for a while, at least, the depth given to Sawamura anchors the film in a coherent emotional reality. It’s hard not to think of Se7en as you watch it, if a more plastic and less textured Se7en, but then that in part speaks to Otomo’s facility with atmosphere.

The movie starts out with promise, introducing us to grisly crimes and hinting at the mysterious but deranged intelligence that planned them. Warning signs appear: there’s a tendency for things to happen too conveniently, as when Sawamura and his assistant Nishino (Shûhei Nomura) realise from circumstantial evidence that an apparent innocent onlooker is actually the killer. But for a while, at least, the depth given to Sawamura anchors the film in a coherent emotional reality. It’s hard not to think of Se7en as you watch it, if a more plastic and less textured Se7en, but then that in part speaks to Otomo’s facility with atmosphere.

The problem is that the movie can’t maintain this feel. Plot twists become increasingly unlikely. Murders are noted briefly, almost in passing. Confrontations between the killer and the cops are staged well, but feel improbable. Sawamura’s put into increasingly tougher situations, but those situations come about because the killer’s given absurd levels of competence.

I’d say, in fact, that the movie really develops problems when we meet the killer and come to understand who he is and why he does what he does. Firstly, he’s off-register, by which I mean that in a movie aiming for gritty realism we’re suddenly faced with a Batman villain — manic, overly brilliant, the product of an operatic origin. Northrop Frye, in the Anatomy of Criticism, wrote about the different modes a story can have; to vastly over-simplify, in a mythic story heroes are wildly greater than others around them, in a romantic story (an adventure story) they’re still superior but less so, in a high mimetic story they’re superior to others but not to the world around them, and so on. Museum is mostly a high mimetic story, with a basically realistic world and a hero who’s exceptionally sharp although flawed; but the villain is a refugee from a romantic story, vastly more gifted than Sawamura to the point where he doesn’t seem to belong in the same story. He’s got a gothic skin condition and a gothic villain’s brooding genius, along with a gothic origin story. Those archly romantic characteristics don’t gel with the noirish world of the rest of the movie.

Secondly, and perhaps more damning, he’s also a cliché. He’s a killer who thinks of his crimes as works of art, which hasn’t been novel at least since 1827 (and De Quincey’s “On Murder Considered as one of the Fine Arts”). A knock-off from the Hannibal Lecter school of psychopaths, he shows that intellectual Japanese serial killers, like those in the West, listen to Western classical music. Much as the movie strains to build a theme around him, he’s simply too generic to carry the weight.

Secondly, and perhaps more damning, he’s also a cliché. He’s a killer who thinks of his crimes as works of art, which hasn’t been novel at least since 1827 (and De Quincey’s “On Murder Considered as one of the Fine Arts”). A knock-off from the Hannibal Lecter school of psychopaths, he shows that intellectual Japanese serial killers, like those in the West, listen to Western classical music. Much as the movie strains to build a theme around him, he’s simply too generic to carry the weight.

The end of the movie reaches for a kind of operatic emotional scope, with Sawamura put in the position of having to make terrible choices; the acting strains to capture a sense of grandeur and tragedy, and doesn’t quite reach it. The movie hints at grand guignol horror out of an Elizabethan revenge play, then backs away in a move that oddly feels more tasteless than if it had followed through. The last moments try to set up a horror-movie ending, with violence and evil persisting into the future, but the twist is too pat.

That said, the movie does at least try to say something about the nature of evil. The problem is that the plot undercuts the theme. Again, the larger-than-life villain makes it impossible to believe that we’re seeing a credible story about real horror. Had the character been toned down, it might have worked; had the movie been more of a fable, it might have worked. As it is, the movie’s not just mixing tones, but also works in a series of plot twists that leave it overly complex and overly contrived — not to mention almost two and a quarter hours long. I presume these twists and connections were included in the name of fidelity to the source material, but I wonder if some streamlining might have been useful here.

I will say that in all those narrative complexities are a lot of character details. Backstories are developed, perhaps too much so, but it does help Oguri and Ono play their characters with a strong sense of realism. We know who they are and why they got together and why they split up. Ono’s Haruka Sawamura, in particular, is given a lot of meat in her background. And yet, again, it feels out of tune with the over-the-top climax. The registers keep clashing, and even good ideas feel off.

And there are good things in this movie. It’s shot and composed very nicely. The image of the villain in a frog mask works surprisingly well. The observation that the villain only kills when it’s raining is remarkably effective at creating a sense of dread whenever the weather changes in the film. Generally I found Otomo was able to build atmosphere well and choreograph confrontations with clarity and a sense for the movement of characters in physical space.

And there are good things in this movie. It’s shot and composed very nicely. The image of the villain in a frog mask works surprisingly well. The observation that the villain only kills when it’s raining is remarkably effective at creating a sense of dread whenever the weather changes in the film. Generally I found Otomo was able to build atmosphere well and choreograph confrontations with clarity and a sense for the movement of characters in physical space.

There are good ideas in the film, too. The problem is, the ideas are for two different movies, and they never really harmonise. It’s quite possible that they work together more effectively in the source material, where more space could be given to more ideas, or at least the proportions might be different. As it is, the first half or so of the movie strikes me as relatively effective, if unoriginal. But the second half can’t follow through. As a whole, Museum’s not uninteresting at points, but is at best an interesting failure.

Looking back over my day, it hadn’t been the most successful — but sometimes in art one pays for all. I usually think that if I’ve seen one excellent movie in a day, then the day’s not gone to waste. So it was here. And I had so many more films to come that I could still only feel excited about the promise of the festival: what else was waiting for me? Museum had ended slightly after midnight; in barely twelve hours the movies would start playing again, and I’d begin to get my answer.

(See all my 2017 Fantasia reviews here.)

Matthew David Surridge is the author of “The Word of Azrael,” from Black Gate 14. You can buy his first collection of essays, looking at some fantasy novels of the twenty-first century, here. His second collection, looking at some fantasy from the twentieth century, is here. You can find him on Facebook, or follow his Twitter account, Fell_Gard.