Star Punk Story Building in Interplanetary Hunter

I caved and bought some old Pulp.

I couldn’t help it. I was at Eastercon and in the dealers room, and there was Durdles Books with shelves and boxes that took me back to my early teens trawling used bookstores and charity shops for volumes with spaceships on the cover.

And since I started writing my The Eternal Dome of the Unknowable series, I’ve been exploring the roots of what I call Star Punk, the covers were cool… so I came home with some faded paperbacks of yesteryear.

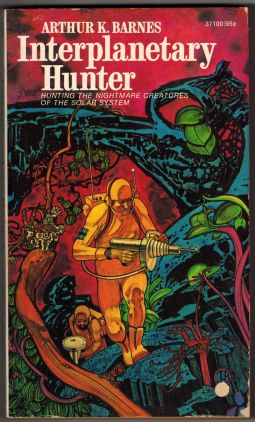

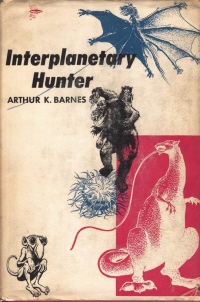

One of these was Interplanetary Hunter by Arthur K Barnes.

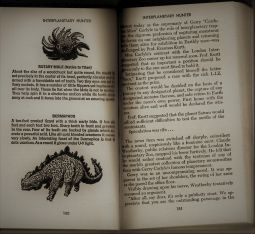

What hooked me was the lovely Monster Manual-style insets describing the various creatures. It was actually published before roleplaying was thing in 1956 (mine is the 1972 Ace reprint), and compiled from stories that went out in magazines from 1937-1946, making it technically Golden Age.

And it tells.

It’s definitely in the category of classics you shouldn’t recommend to young people (I talked about this in my first ever BG article!). It’s a good light read, the style and lead-in may be fast and furious — pulpy goodness — but it suffers from Quaint Future and some Quaint Delivery, including excruciatingly detailed science and pseudoscience, complete with equations.

Most striking is its ambivalence to the female lead, Gerry Carlyle. Even the 1970s cover hides the fact that a woman drives the action!

The original publishers worried about how Gerry would go down with their mostly teenage male audience. However, she turned out to be wildly popular in a way that possibly prefigures the Lara Croft formula.

She even made enough of a lasting impact to merit a portrait in Ron Miller’s Firebrands: Heroines of Science Fiction and Fantasy(*)

Gerry is very much a mid-2oth century liberated woman who’s carved out a niche for herself as a ruthless interplanetary hunter. She captures exotic alien beasts to stock the zoos of Earth, commands the loyalty of a rough tough crew, and owns at least one spaceship. Her escapades and beauty have made her a celebrity in her own right — think Amelia Earhart does Pirates of the Caribbean in Space. According to the ebook version‘s introduction, she was modeled on ace animal collector and memoirist Frank Buck.

We mostly see Gerry through the eyes of her fiancee, Tommy Strike. He’s a capable operator, but very much a sidekick and second-in-command. There’s a little power struggle, especially at first, but mostly it isn’t she-wears-the-trousers comedy. Their occasional conflicts are more about “you may be my boyfriend but this is my organization and I’m the boss” and “please don’t get killed stupidly because I love you” than gender roles. At one point they both acknowledge that they will live and die as adventurers. Really, there’s no Calamity Jane gingham dress moment.

So far so Wonder Woman.

Alas, it’s as if the narrative has been given a male chauvinist once-over! Despite being an experienced leader used to life-and-death decisions, Gerry is usually “a girl”. She even stamps her feet and I swear she pouts at least once. We are treated to patronizing ruminations on the nature of women (cringe)! And Tommy often uses a manly kiss to silence her at the end of a story. No, not a book for a younger or new SF reader. Even so, it’s still a good read, crisply written and the sort of sense of space you get from Edmund Hamilton.

However, what’s interesting about this now obscure paperback is that each of the five stories masterly demonstrates an engaging SF&F technique for writing quests: (1) the group engages in one or more running human conflicts in an SF setting, on their way to (2) the climax of one or more pure SF conflicts (essentially, take on the story “Boss”) , and (3) have one conflict resolve the other. Where there are several conflicts, one out of each category will be primary.

This is essentially how The Hobbit works, both book and movie.

The human(oid) running conflicts are “novice hero versus adventure” (primary) and “party versus hostile environment”. These are generic enough that it would still work without the Fantasy elements: you could dump the traveling portion of the story into Dark Age Europe, swap in different flavors of barbarians, and it would read fine. The dragon and the treasure at the end, however, for all that they are allegorical, create pure SFnal conflicts: “party versus dragon” and “party versus bad vibes exuded by the treasure” (primary, because the dragon foreshadows this). The Lord of the Rings is similar, except that, unlike Smaug, Sauron knows the party is coming and opposes the quest, meaning that the conflicts begin interacting early.

So back to Interplanetary Hunter. It’s really five linked stories:

In the first story, Venus, we meet, Tommy Strike stationed in a lonely Venusian trading post. Gerry and her team arrive to bag one of the local critters. The human running conflicts are “arrogant explorer versus established guide” (primary) and “party versus exotic environment”, both familiar from just about every Tarzan movie ever made. The SFnal conflict is “expedition versus alien” and presents a puzzle with a poignant resolution. The result is as if Robert E Howard had gotten hold of a Ray Bradbury outline.

Jupiter is more complicated. Tommy, now second-in-command, takes a team after a mysterious “fire demon” on one of Jupiter’s moons, not realizing his equipment is sabotaged. Gerry rushes to his rescue, but can only reach him with the help of the frontier pilots of lawless Ganymede, haven for wanted men as long as they ply the perilous routes around the gas giant. The resulting sequence really does feel like Pirates of the Caribbean. However, capturing the exotic fire demon hinges on its SFnal nature. So the primary human conflict is “Gerry vs practicalities to get to Tommy”, and the SFnal conflict is “expedition versus alien”, which is gloriously twisty-turny, and no, no spoilers in case you read it.

Neptune actually sends our heroes on a rescue mission to Triton… or is it a trap? The primary human conflict is “Heroes versus scheming Pirates”, but several secondary ones are foregrounded as the conspiracy unfolds. The SFnal conflict is “expedition versus hostile environment,” survival being down to pure (pseudo?) science.

In Almussen’s Comet we encounter the mysterious denizens of a Clark Ashton-Smith-style comet as it hurtles toward the sun. The twist is that, to get there, Gerry must team up with a hated rival who is a movie maker. The rival not only gets in the way, he’s also determined to misrepresent her in his latest project. This gives us “professionals versus journalists,” and, again, “expedition versus alien.”

In the finale, Saturn, with her career at stake, Gerry is manoeuvred into racing a (chauvinist) rival to bring back an acid-secreting Dermaphos from Saturn: “expedition racing versus expedition” and “expedition versus alien.” It’s a rip roaring tale, with reversals slamming into each other like a freeway pileup. Two conflicts interact in ways that are as gripping as they are, ultimately, amusing.

In a nutshell, these stories are:

A human conflict in space leading to SFnal conflict, also in space.

That’s not the same as “Mutiny on the Bounty but they have to fight Robot Ninjas at the end” like a dire YA I once reviewed (“Blah Blah Blah” by Thingy Whatsisname). The “in space” part is as important for the human conflict as it is for the SFnal one.

This structure works for several reasons.

A human conflict is easier to keep going than a pure SFnal one. We see this in Elizabeth Moon’s Vatta’s War — a space battle can last a chapter, but a feud can last a series. It’s also more engaging to the reader, because of empathy and resonance, but also because the reader already understands human things and can have fun trying to solve the plot, or second guessing the characters. Finally, the human conflict brings to life the SF setting, as characters we care about seek to manipulate their environment for advantage, or merely survival. When we get to the big SFnal conflict, we’re already tuned in and ready to make some kind of sense out of it.

There’s are also a creative advantage to this structure; you can revive old tropes and dial them up to 11.

This works particularly well in (what I’m doggedly calling) Star Punk because a spacefaring setting provides the physical space such that people not unlike us can experiences tropes more appropriate to pre WWII settings. For example, in the first story, we have the loneliest of Lonely Trading Posts, not in some corner of Africa, but on a different planet millions of miles from Earth. Later, we also have Pirates, Lawless Ports, Perilous Expeditions, and Racing Explorers, all with the highest possible stakes. Of these, only the first two would, with a little tweaking, make much sense in a 21st century setting. Technology has already abolished the prerequisite distance and isolation.

Intriguingly, in doing this, you can rehabilitate some old favorites by shedding their colonialist/racist baggage. The Venusian natives really are the Other because they really are aliens, not just a human culture thoughtlessly stereotyped to fill the Other slot. The Lost Race on the comet doesn’t say anything unfortunate about, say, civilization and ethnicity, because they are weird aliens who live on a comet with other weird aliens.

Most of us like the old Pulp tropes, not because of the world view they embody, but because of the predicaments and emotions they generate — we all faced the Other who does not regard us as a person the first time we stepped into the schoolyard. I doubt that this was Barnes’ intent, but it is an invitation to mine my mouldering collection of Biggles books for Traveller scenarios and more.

I know that I once swore off old genre books, however the good ones have the double advantage of being short, and thus more transparent when you want to pick at their bones. You can find a used copy of Interplanetary Hunter via Amazon, or get hold of the first ebook free. but you might also try your luck with Durdles Books…

M Harold Page is the Scottish author of The Wreck of the Marissa (Book 1 of the Eternal Dome of the Unknowable Series), an old-school space adventure yarn about a retired mercenary-turned-archaeologist dealing with “local difficulties” as he pursues his quest across the galaxy. His other titles include Swords vs Tanks (Charles Stross: “Holy ****!”) and Storyteller Tools: Outline from vision to finished novel without losing the magic. (Ken MacLeod: “…very useful in getting from ideas etc to plot and story.” Hannu Rajaniemi: “…find myself to coming back to [this] book in the early stages.”)