Some Historical Novels for Readers and Writers of Fantasy and Science Fiction

When I was an undergraduate at the University of Houston, I minored in history. My professor of the history of the Old South explained the difference between an antiquarian and a historian thus: An antiquarian will know lots of facts and figures and data; a historian will interpret the information to seek what it means. For this reason, I have always considered historical fiction inextricably linked to the work of historians. As historians are inextricably linked to the work of fantasists, the transitive property holds that historical fiction is an important part of the world of fantasy fiction. The past is a ripe field for the imagination, and full of stories.

When I was an undergraduate at the University of Houston, I minored in history. My professor of the history of the Old South explained the difference between an antiquarian and a historian thus: An antiquarian will know lots of facts and figures and data; a historian will interpret the information to seek what it means. For this reason, I have always considered historical fiction inextricably linked to the work of historians. As historians are inextricably linked to the work of fantasists, the transitive property holds that historical fiction is an important part of the world of fantasy fiction. The past is a ripe field for the imagination, and full of stories.

It’s actually very difficult to separate the historical fiction from what is generally considered the fundament of realist fiction, or whatever fiction mode it takes as its fundament. The widely-acknowledged first work of what we call the modern novel described as a novel, Don Quixote, was about a character who read to much historical fiction, hearkening back to a different time. The character of Don Quixote, himself, became so enamored of the past that he invented his life into a historical re-enactment. He was perhaps the original member of the society of creative anachronism.

Even such Ur-texts as The Illiad, The Odessey, and The Epic of Gilgamesh seem to be acts of historical invention in their own time. Telling the story of “where we came from” is one of the fundamental stories that drives narrative forms, because it seems to speak to where we ought to go, and who we ought to be. The past tense is a standard mode. Nearly all fiction is driven by a sense of the past, hopefully one that bridges to a future.

Our relationship to history is a fraught one. We carry our preconceived notions of reality, as readers and writers, inside of our judgment of books and characters. History doesn’t have to be plausible, but fiction does. To truly study history, we almost have to abandon those ideas, and embrace ways of thinking that are not natural to us. One of the limitations of historical fictions versus non-realist work is that we don’t really approach the characters as intellectual equals, when we should. When the villagers in The Scarlet Letter demand the A upon Hester Prynne, we are pre-made as modern individuals to see her as the noble martyr, and them as morally repugnant hypocrites, without even understanding the sense of helplessness against a harsh universe that drove their fear of such misbehaviors, even into the horrors that they committed. We simply don’t empathize with the villagers. But, to bring to life, and to comprehend, history and where we came from, we must challenge ourselves to take people seriously, even when they are on the wrong side of our version of history.

[Click the images for bigger versions.]

An author that embodies this is a fantasy author, but he is as close to a historical fictionist as it is possible to be, while still being solidly a fantasist. Guy Gavriel Kay writes meticulously researched historical fantasies that use the tools of the fantasist to make beliefs and folktales and miraculous wonders physically present inside the history books, and to hide our own prejudgments about terms and cultures behind a veil of the unreal. Thus, no one is allowed to look down upon these historical figures as believers in foolishness when the shambling mound appears and the warhammer is sacrificed to appease the spirit of the old forest. The magical beliefs are physically present. And, when that forest of magic is pushed back over time, becoming a quotidian place more resonant of modern life, the reader physically feels the shift in known reality that emerged in human consciousness out of the beliefs of the old world passing away. (This was in The Last Light of the Sun, by the way, which was an excellent look at the Norman raids of England, and the rise of the culture of mounted knight.)

|

|

|

How did people think before us? This is one of the questions I try to answer by reading historical fiction. In particular, when I am reading older books that are, themselves, about older times, there’s two layers of thought happening on the page. First, there is the layer where the characters in the story live out their lives and fears. Second, the author, from their own vantage point in history, projects their will and ideals back, consciously or not, into a place and time that is lost. Gone With the Wind is a masterpiece worthy of continued reading. The sweep and scope of the book, and the way women are portrayed in that tumultuous time doesn’t just tell me about Scarlett O’Hara and her sisters and all the women around her. It also speaks to the rise of feminist ideals by a female journalist who had faced all the sexism the world could throw at her, professionally, and still had to make her way in a man’s world. I feel a sense, in that book, that the parts of Margaret Mitchell’s sense of self and feminine identity that are animated into the bones and moments of history are also the parts that speak the deepest truth about what is universally human between those poles. Exploring the differences is worthy of pursuit. What ends up on the page, moreso in fiction than anywhere else, is about the creator’s notions. So, when reading historical fiction, we are not just seeing how people thought, felt, and acted at some point in history. We are also reading how someone thinks about that, feels about that, and what parts are meant to speak to us as intended by a creator.

One of my favorite writers of historical fiction often wrote specifically about his island nation among the volcanoes and the ice. Haldor Laxness won a Nobel Prize for his astonishing fictions, that take as a backdrop life among the shepherds and peasants of historical Iceland. Two books that stand out as potentially very interesting to readers and writers of genre fiction are Iceland’s Bell, a dark comedy and pastoral story about a wife-beating shepherd, a beautiful, elfin woman, and the pages of books that were stuffed in the shoes and the walls of the starving common folk. The sheperd’s peripatetic comic pastoral becomes this far-ranging journey across Europe in a period of time where the modern world isn’t even close to coming together, and could fall apart at any moment, and the identity of a people is being lost to poverty and indifference. Another amazing work by Laxness that contains multitudes is Independent People, that begins with the curse of a witch and ends with the curse of a witch, and in between a stoic shepherd pushes back against the brutal elements with his own sense of right and wrong, a morality that consumes his family and his future worse than the witch’s curse. These tales are structured like Icelandic epics mashed with modern novels. They carry a past and a future simultaneously, a history of Iceland and an argument about what the little island nation had better learn before its too late – what all of us had better learn about love and interdependence and a darkly comic cosmic indifference.

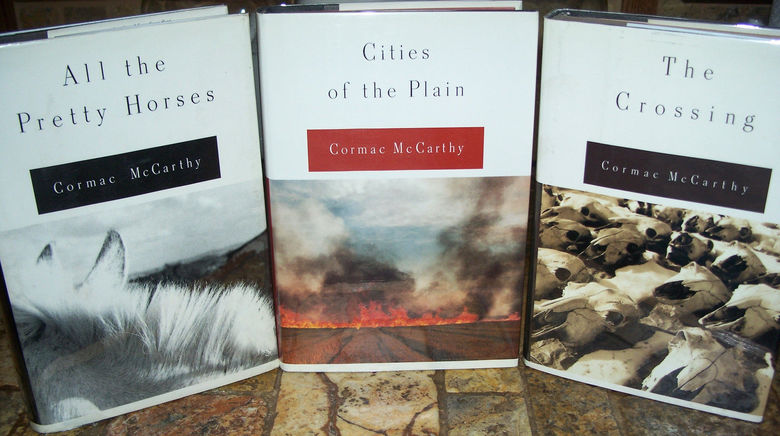

The Border Trilogy, by Cormac McCarthy

Modern, living authors are continuing to turn to history for inspiration. The thing is, history changes with the decades. Reading westerns, just as an example, fifty years ago is a story of white men dominating the difficult landscape, and coming to peace with it. The Border Trilogy by Cormac McCarthy, a revolutionary document in the genre of westerns, tried to deal with the violence that men do to the people, place, and animals all around them and find some kind of peace in it. These days, it’s hard to read Westerns without the ideas of white supremacists polluting the water. White men came in and murdered a lot of people to take their land. That it seemed empty and uninhabited had more to do with the diseases that wiped out thousands if not millions of Native American lives as a sort of vanguard to the actual contact with the white humans that came after their diseases swept through. To write compellingly about history in the American west means dealing with the racial ideation that polluted their world, and continues to pollute ours.

In this, good examples of how to do it right can be found in Sarah Canary, by Karen Joy Fowler. This is a story about a woman who probably escaped from an asylum, helped along by an early Chinese-American who is constantly aware of the tenuous nature of his continued personal safety in the rough community of nineteenth-century California. The reader is never permitted to forget the very real possibility of a man getting lynched for the crime of trying to help a white woman. The story is wrapped in a mystery, of course, about the true identity of this mad, wandering woman, and if she is a woman at all, or else some other sort of celestial form. There is also, in this text, the question of how history treated the lowest members of society, the insane. This is an important question when constructing fantasy worlds. In a time before modern medicine, how did society deal with the disabled, the handicapped, the mentally ill?

The race war at the heart of American history, the pulsing, wicked ooze that wraps its tendrils around the story of our Republic, began early. Also, at the heart of our country’s foundation was a great spiritual revival, like a madness that sweeps in occasional waves across our lonely plains. Susan Stinson wrote beautifully about race and faith in her novel Spider in a Tree. One of the great advantages of fiction versus other, drier forms of history, is how the different elements that a historian like to discuss will intersect into the lives of the characters. Slavery, the sacred, the challenge of survival, and the insular, occasionally spiteful community of early America is all wrapped up in the life and lives of the family and house slaves of Jonathan Edwards, a powerful fire and brimstone preacher from American history. At once a man of God, and an owner of living men and women, balancing the aspiration to the holy with the difficult and often horrid reality of life among the hypocritical Puritans is well-wrought, and carries many complex ideas wrapped in beautiful, symbolic prose.

|

|

|

To know American history is to read American historical fiction, where authors see the problems of the world back at the places where they were born as institutions and ideas. There is hardly a single decade of life in this country not thoroughly covered by brilliant historical fictions. Pick a decade or a moment of interest to you, and then dozens and hundreds of books will appear. My opinion on most American historical fiction is that work by more contemporary authors is often superior to the work of those long dead because the shift in society towards liberalism and an acceptance of the equality of the races has changed the nature of our understanding of what came before us to something more closely resembling the truth over a whitewashed version of events.

Speaking of whitewashing, the great absence of historical fictions that are only recently being addressed by working authors involve the world where most people are not white. Take Africa, as an example: For centuries empires rose and fell immune to the influences of Europeans. So much of what happened to shape the modern world happened in Africa in cultures and communities that most of my countrymen couldn’t find on a map. Timbuktu was the cradle of science and culture for hundreds of years. The great Christian thinkers that have gone on to shape all Christian theology take as their foundation stone an African, St. Augustine of Hippo. Things that we take for granted, now, like wheat and coffee and cotton, were cultivated and developed by brilliant African farmers for thousands of years and we reap the bounty of their genetic breeding efforts. There is plenty of work being done on ancient Egypt, but once Greece and Rome rise in the world, the story of Africa is hard to find. This is true of everywhere in the world where the Colonial story is the dominant one in history books and fictions.

For this reason, I recommend reading the work of history as written by authors who speak of their own communities’ histories. One favorite of mine, and perhaps one of the most well-crafted books I’ve read to date, is Half of a Yellow Sun by Chimamanda Ngozi-Adichie. It tells the story of a revolution in Nigeria that isn’t even a footnote in the history books, in our country, yet so much pain and misery and hardship resulted from that dark period of recent history. It’s hardly the only brilliant book explicating histories that our own culture often doesn’t care to see, but it’s a stand out among them, and a compelling argument for a continued quest to read the histories of the world we have lost through our own failure to see beyond what is ourself.

Historical fiction is a unique tool to do exactly that. It allows us to see the world through eyes that are not like ours, and to construct an argument for how to interpret history, and how to shape our own destiny off the past that possibly was this way. It is so closely aligned with realist fiction as to be inextricable from the general genre of the mainstream narrative. It is also a close bridge to the genre of fantasy and alternate history. Every work of historical fiction, after all, is a fantasy of how things were. It is a magical reinvention of a place and time and people through the power of story.

J. M. McDermott is the author of Last Dragon (2008), Maze (2013), and the Dogsland Trilogy (Never Knew Another, When We Were Executioners, and We Leave Together). Matthew David Surridge called Never Knew Another “literary fantasy that recalls the work of Ursula Le Guin or perhaps Samuel Delaney… tremendously impressive.” His novella The Fortress at the End of Time, which Andrew Liptak called “an essential read… feels like it’s a throwback to the era of classic science fiction from authors such as Frank Herbert or Ursula K. Le Guin, but never dated,” was published by Tor.com on January 17, 2017. His last article for Black Gate was We Live In Small Worlds.

Great post. I greatly appreciate the points you bring up here.

In terms of my own academic fields, there are some great strides being made in addressing the lack of research on the effects of African thought on Christian theology. Some great works here include How Africa Shaped the Christian Mind by Thomas Oden and Justo Gonzalez’s two volume history of Christianity also emphasizes the benefits of Africa upon this religion.

I read historical fiction from time to time, usually stuff that scratches much the same itch I get from fantasy — Harold Lamb’s Cossack stories, e.g., are proto-sword-and-sorcery, but without the sorcery. And I remember back in the 1980s & 1990s there were a bunch of big, fat historical novels (Gary Jennings’ Aztec, Nicholas Guild’s The Assyrian, Ken Follett’s Pillars of the Earth, e.g.) that were big and bloody and filled with sex, kind of prefiguring the way Game of Thrones changed epic fantasy.