Rich Playboys, Mad Scientists, and Venusian Monsters: The Best of Stanley Weinbaum

A few short years ago, here at Black Gate, John O’Neill did several posts on Del Rey’s Classic Science Fiction series. Those posts were loving, nostalgic homages.

A few short years ago, here at Black Gate, John O’Neill did several posts on Del Rey’s Classic Science Fiction series. Those posts were loving, nostalgic homages.

I have never been a huge sci-fi book fan. Fantasy and horror are more my thing. Yet, I found those posts really intriguing, especially the cool covers. I had read some of the stories of certain of these writers, but by and large John’s posts introduced me to most of these authors for the first time. After reading a couple, I was hooked and eventually tracked them all down through eBay and Abebooks.

As a newcomer to these books, and to many of these authors, I thought I would give a review of each. As with John’s original posts, I hope these reviews inspire some newer readers to seek out some of these older treasures, or at least to track down some other works by these authors.

Before reviewing our first volume, let’s get a little background on this series. The Internet Speculative Fiction Database (isfdb.org) refers to these books as Ballantine’s Classic Library of Science Fiction. However, I can’t find that designation on any of the books so I’ll simply refer to them as “Del Rey’s” (an imprint of Ballantine) “Classic Science Fiction” series, just like the covers say. This series began in the early seventies and continued to be published up through the eighties, sometimes with multiple printings of certain volumes. There were twenty-two books published in all.

Each book in this series was a collection of short stories highlighting a single author within the Del Rey publishing fold. According to John O’Neill, this was one way for Del Rey to promote the authors in their stable (especially de Camp, Eric Frank Russell, and others). That’s why there are no volumes dedicated to Asimov, Heinlein, Clarke, etc. None of those “big guns” were Del Rey authors. That’s not to say that there weren’t some heavy hitters in this series though. Writers like Philip K. Dick and Fritz Leiber, to name only two, have dedicated collections within.

I thought it might be best to go through this series in chronological order of publication. Each post will focus on one volume. My main goal is try to give some brief reviews of some of the stories within, at least those that struck me as the most enjoyable, but I’ll also give my overall impressions about the book, and writer, as a whole.

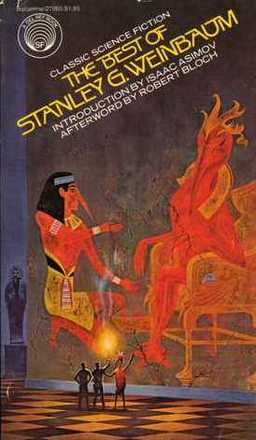

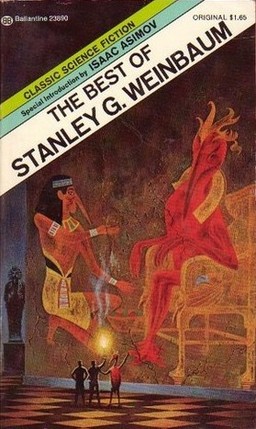

The first book published in Del Rey’s Classic Science Fiction series was The Best of Stanley Weinbaum (1974). The cover painting is by Dean Ellis, and the first two editions of this book had a different style of font for the title. I’ve personally tracked down two copies of this book but both are 1979 third printings with the cover font that matches the rest of the series.

Isaac Asimov (1920-1992) does the introduction to this volume and his praise for Weinbaum is quite high. He refers to him as the “Second Nova” of science fiction, his first nova being Doc Smith and his third being Robert Heinlein. Another thing that also makes this praise so high is that Weinbaum died at a very young age (1902-1935) and had only been publishing in the pulps for just a few short years before his death. Yet his stories were incredibly popular and his unique genius was widely recognized. As I heard at a panel a few years ago at Pulpfest, Weinbaum was often reprinted in Astounding Stories because he was “the gift that kept on giving” (i.e. even his reprinted stories sold magazines).

Any informed discussion of Weinbaum has to focus upon his many intriguing conceptions of alien life. This is particularly true in one of his most famous recurring alien characters Tweel, who appears in this volume in Weinbaum’s most famous story “A Martian Odyssey,” and also in “Valley of Dreams.” Both of these stories take place on Mars centering upon the astronaut and astronomer Captain John Harrison. In “A Martian Odyssey” Harrison happens upon and befriends Tweel who is a stork-like humanoid that can only communicate in chirps and whistles. “Tweel” is the closest Harrison can arrive at for his name. To give you a feel of just how inventively alien Weinbaum could conceive of his creatures, Tweel interestingly travels along by mostly jumping large distances (i.e. tens of feet) and landing in the ground beak first like a javelin. He then takes his stork-like nose out of the ground and repeats the process.

Though Tweel is probably Weinbaum’s most lovable and popular alien, throughout many of his stories Weinbaum does a wonderful job of coming up with many incredibly diverse creatures, from all-encompassing doughy blobs (“Parasite Planet”), to seemingly eternal brick-making pyramid builders (“A Martian Odyssey”), to giggling, balloon-headed loonies and rat like creatures with near human intelligence (“The Mad Moon”). And this just scratches the surface.

As a comparison for feel, H. P. Lovecraft’s alien creatures were also utterly other and weird, but to the point that they often evoked horrific responses. Weinbaum’s creatures, on the other hand, are so different that they tend to simply pique one’s interest. That’s not to say that his creatures can’t be menacing and horrific. For example, in “Parasite Planet” and “The Lotus Eaters” the main characters are stalked by whooping and cackling Venusian monsters that hide in the dark. Their unseen and incessant hyena-like laughter put the reader on edge as you worry for the main characters’ escape. But, as with all Weinbaum’s aliens, you tend to be more intrigued than horrified by what he has cooked up.

Given the alien encounters on other planets, it should be clear that many of Weinbaum’s stories are typical sci-fi pulp fare, including brawny American men (usually a combination of scientist and pilot) going to faraway lands to explore, discover, and usually ending up saving damsels in distress. But there is some real diversity and depth to Weinbaum’s stories as well.

“The Adaptive Ultimate” focuses upon two (not quite mad) scientists who more than push the ethical borders. Finding a hormone within very adaptive insects, these scientists develop it and inject it into a dying woman with — surprise! surprise! — unexpected and unwelcome outcomes. The story follows their attempt to undo their mistake.

Weinbaum has several sets of recurring characters in (I take it) different worlds. In a couple of stories, “The Worlds of If” and “The Ideal,” rich playboy Dixon Wells rather stumbles upon some new discovery from the great scientist Dr. van Manderpootz, Dixon being a former student of said scientist. These two stories are a bit silly, having something of a slap-stick (a la P. G. Wodehouse) humor and feel to them, though set in a sci-fi universe. But Weinbaum sets up some rather heavy themes in these stories as well. In “The Worlds of If” Dixon’s habit of lateness is introduced as a seemingly innocuous vice. But Manderpootz’s newest invention allows him to see into possible futures. Upon witnessing a perfect love in one of these possible futures, Dixon attempts to bring this possibility about in real life but ends up losing out because of — you guessed it — his lateness. Rather than being a cutesy ending, this story has something of a Twilight Zone episode ethical heaviness to it. You can almost hear Rod Serling give the moral of the story at the end. Quite unexpected given the setup.

Weinbaum’s stories could be very diverse. “Pygmalion’s Spectacles” is something of a philosophical thought experiment and drifts, in my opinion, more into fantasy than being true sci-fi. “Shifting Seas” is sort of an early catastrophe story envisioning the earth as being affected by a mass of erupting volcanoes. And for most of “Proteus Island,” the story reads more like a horror tale from William Hope Hodgson, a deserted island with inexplicable creatures lurking in the dark.

Weinbaum’s stories could be very diverse. “Pygmalion’s Spectacles” is something of a philosophical thought experiment and drifts, in my opinion, more into fantasy than being true sci-fi. “Shifting Seas” is sort of an early catastrophe story envisioning the earth as being affected by a mass of erupting volcanoes. And for most of “Proteus Island,” the story reads more like a horror tale from William Hope Hodgson, a deserted island with inexplicable creatures lurking in the dark.

As with any older writer, there are plenty of old-fashioned elements that any contemporary literary critic can have a heyday trouncing. In addition, Weinbaum (an engineer himself) sometimes like delving into paragraphs-long, though somewhat plausible, pseudo-science explanations of fantastic or sci-fi pheonemona. But, in sum, Weinbaum’s stories are inventive and interesting. They are adventurous, page-turners that really stretch your imagination. The result is a menagerie of enjoyable reads.

Robert Bloch (1917-1994) gives an afterword in this volume describing his early friendship with Stanley Weinbaum. The details here are touching, but again highlight the imaginative skills of Weinbaum.

If memory serves, I think John O’Neill’s fifth post on the Del Rey Classic Science Fiction Series covered The Best of Stanley Weinbaum. When I first read this book I fell in love with Weinbaum. Returning to this book again for this post, I found these stories to be exceptional again — not a wasted read! Though Stanley Weinbaum’s writing tenure was brief, I can see why Asimov saw him as one of the great novas of science fiction writing.

Our previous articles on Stanley Weinbaum include:

Take Me Down to the “Parasite Planet” (Where the Grass Is Really Disgusting) by Ryan Harvey

Fredric Brown, Stanley G. Weinbaum, and Appendix N: Advanced Readings in D&D

Vintage Treasures: The Best of Stanley G. Weinbaum

And our previous coverage of the Classics of Science Fiction line includes (in order of publication):

- Rich Playboys, Mad Scientists, and Venusian Monsters: The Best of Stanley Weinbaum by James McGlothlin (1974)

- A Neglected Master: The Best of Henry Kuttner by James McGlothlin (1975)

- A Shaper of Myths: The Best of Cordwainer Smith by James McGlothlin (1975)

- Smugglers, Alien Vampires, and Dark Dimensions: The Best of C. L. Moore by James McGlothlin (1976)

- Space Colonies, Interstellar Fleets, and The Martian in the Attic: The Best of Frederik Pohl by James McGlothlin (1976)

- Classic SF from One of the Twentieth Century’s Great Masters: The Best of John W. Campbell by James McGlothlin (1976)

- Shark Ships and Marching Morons: The Best of C. M. Kornbluth by James McGlothlin (1977)

- Drawing Out What it Truly Means to be Human: The Best of Philip K. Dick by James McGlothlin (1977)

- Wit and Play in Classic Science Fiction: The Best of Fredric Brown by James McGlothlin (1977)

- Wings, Wind, and World-Wreckers: The Best of Edmond Hamilton by Ryan Harvey (1977)

- Dead Cities, Space Outlaws, and Planet Gods: The Best of Leigh Brackett by Ryan Harvey (1977)

- From the Pen of a Great Pulpster: The Best of Robert Bloch by James McGlothlin (1977)

- Germ Warfare, Sentient Planets, and Dark Age Alchemy: The Best of Murray Leinster by James McGlothlin (1978)

- Dinosaurs, Mermaids, and Haunted Lumber: The Best of L. Sprague De Camp, by James McGlothlin (1978)

- The Best of Jack Williamson by John O’Neill (1978)

- Davey Jones, Alien Spores, and Riding on a Comet: The Best of Raymond Z. Gallun by James McGlothlin (1978)

- Gods, Robots, and Man: The Best of Lester del Rey by Jason McGregor (1978)

- Space Empires, Ruined Civilizations, and Lovable Aliens: The Best of Eric Frank Russell by James McGlothlin (1978)

- The Best of Hal Clement by John O’Neill (1979)

- The Best of James Blish by John O’Neill (1979)

- Vampires, Frozen Worlds, and Gambling With the Devil: The Best of Fritz Leiber by James McGlothlin (1979)

- The Best of John Brunner by John O’Neill (1988)

See all of our recent Vintage Treasures here.

By coincidence, I have a copy of this one, having picked up a second hand copy a few years back. The Robert Bloch collection is the only other one I have.

I read a story by Weinbaum called “The Circle of Zero” (1936) which I thought was amazing—it’s nothing less than a multiverse story; the earliest I’ve come across. I would have expected it to number among his best. No matter, though: it can be read free on Project Gutenberg.

@dolphintornsea

Thanks for the recommendation. I haven’t read that one. I think all of Weinbaum’s stuff is free online now.