Superheroes in Prose: A City-Smashing Interview with the Editors of the New Anthology Tesseracts Nineteen

Get a load of this: Superheroes! Supervillains! Superpowered antiheroes. Super scientists. Adventurers into the unknown. Costumed crimefighters. Mutant superterrorists. Far-future supergroups. Crusading aliens in a strange land. Secret histories of covert superspies… and more! All in a Canadian setting.

Get a load of this: Superheroes! Supervillains! Superpowered antiheroes. Super scientists. Adventurers into the unknown. Costumed crimefighters. Mutant superterrorists. Far-future supergroups. Crusading aliens in a strange land. Secret histories of covert superspies… and more! All in a Canadian setting.

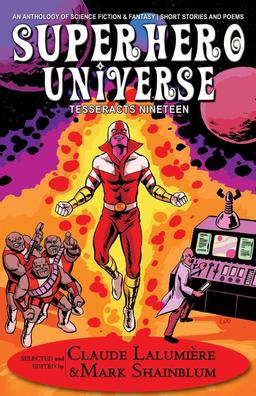

This is the call for stories that went out in 2014 for the anthology Superhero Universe: Tesseracts Nineteen by EDGE Publishing which is launching this month. Its editors are Claude Lalumière and Mark Shainblum.

Claude has edited thirteen previous anthologies, including Super Stories of Heroes & Villains, which was hailed in a starred review by Publishers Weekly as “by far the best superhero anthology.”

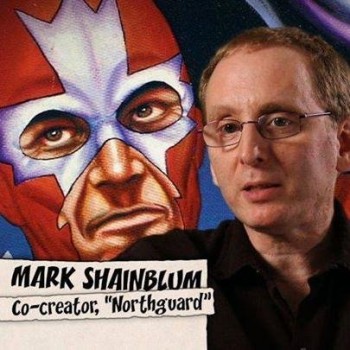

Mark Shainblum co-created the comic series Northguard and the bestselling humor book series Angloman, which later appeared as a weekly strip in The Montreal Gazette. Mark also collaborated on the Captain Canuck daily newspaper strip. I caught up with Claude and Mark for an e-interview.

I recently interviewed Dominik Parisien about his Canadian Steampunk anthology and he had some intriguing ideas about what distinguished Canadian steampunk from the broader genre. What do you think distinguishes Canadian superhero stories thematically from superhero stories in the broader superhero genre? Can’t we all just Hulk-Smash?

Claude: I’ve noticed that superhero fiction by Canadians – whether or not it’s set in Canada – has a strong sense of place, and that often an integral part of the story sees the protagonist trying to reconcile their “super” status or identity with their sense of place.

Claude: I’ve noticed that superhero fiction by Canadians – whether or not it’s set in Canada – has a strong sense of place, and that often an integral part of the story sees the protagonist trying to reconcile their “super” status or identity with their sense of place.

I’ve encountered that theme in some US superhero fiction – most notably, Andrew Fox’s Fat White Vampire Blues – but it’s not as prevalent in US stories while it really stands as a defining characteristic in most Canadian superhero fiction.

Mark: I totally agree with Claude about the sense of place. Canadian writers revel in the chance to set their stories in Canada without having to somehow excuse it. In Superhero Universe, unlike Claude’s previous anthology Masked Mosaic, it wasn’t a requirement that the stories be set in Canada or have Canadian protagonists, but most of the writers did anyhow.

But more than that, I think Canadian superhero fiction is distinct in the same way that Canadian speculative fiction in general is distinct. Our voice is different. We lack the sense of historical destiny about our place in the world that Americans imbibe whether they want to or not. The stories are often more personal and more about relations between individuals than they are about the fate of the universe.

They say that superheroes are indigenous to the comic book environment. They’ve obviously colonized other visual and dramatic media like TV and movies and radio, but what do we gain or lose with exploring superheroes in prose? As editors, what different choices did you have to make to allow for the different medium?

Claude: Superheroes are NOT indigenous to comics. That’s simply where they came grew up and where they were most prominent during the twentieth century. They originated in prose fiction. To name the most prominent examples: Zorro, Tarzan, John Carter, the Shadow, Doc Savage, and Philip Wylie’s Gladiator all predate the first comics superheroes, Mandrake the Magician and the Phantom.

Sure, the formula got perfected in comics, but the Shadow, especially, isn’t lacking a single ingredient: costume, powers, crime-fighting, secret identity. The superhero genre is indigenous to prose fiction, but it’s only recently come back home. For decades, prose editors, especially in SF and fantasy, were particularly disdainful of the superhero genre, but I think its future is in prose. We’ve started to see more and more superhero prose, and as the superhero genre is conquering the cultural landscape, stories and novels that will explore the genre in greater depth are inevitable.

Mark: It’s not just the general archetypes that were established before superheroes made it to comics, but some extremely specific superhero tropes we still have today were invented in the pulps: Superman’s Fortress of Solitude was based on Doc Savage’s retreat of the same name. “Man of Steel” came from “Man of Bronze”.

Batman’s Bat-Signal originated with a very similar signal used to summon the Phantom Detective. Green Lantern’s power ring and the Green Lantern Corps as a whole were derived from E.E. Doc Smith’s Lensmen stories. The whole secret identity shtick was invented for characters like The Shadow, The Spider and The Black Bat. All of these tropes, this “toolbox” of the mystery-man genre already existed and creators like Siegel and Shuster, Bob Kane, Jack Kirby, Joe Simon and Will Eisner were well aware of them.

Batman’s Bat-Signal originated with a very similar signal used to summon the Phantom Detective. Green Lantern’s power ring and the Green Lantern Corps as a whole were derived from E.E. Doc Smith’s Lensmen stories. The whole secret identity shtick was invented for characters like The Shadow, The Spider and The Black Bat. All of these tropes, this “toolbox” of the mystery-man genre already existed and creators like Siegel and Shuster, Bob Kane, Jack Kirby, Joe Simon and Will Eisner were well aware of them.

In terms of telling superhero stories, comics and prose are very different media. It takes pages and pages and pages of prose to describe an action scene that can be illustrated in a single comic book page, so there tends to be less action for action’s sake in prose superhero stories. Prose is by definition closer to the character, more inside her head, and though you can do that in comics too, it’s a more natural mode to slip into in prose. Also, obviously, comics are a visual medium, so the physical appearance of the characters, their costumes and iconography are more front and center.

As for prose editors who disdain prose superhero fantasy but cheerfully accept wizard-and-barbarian or elves-and-orcs fiction, my only response is… huh?

Claude: Actually, the secret identity shtick predates those 1930s heroes. Zorro, most prominently, had it (plus a secret hideout, and so much more that made it almost note for note into Batman and superheroes in general). Even before Zorro, the Scarlet Pimpernel had a secret identity. Elements of the Pimpernel fed into superheroes, but I would hesitate to put the Pimpernel within the superhero lineage without a lot of caveats. Zorro, on the other hand, totally a superhero.

American Superheroes were arguably born from a post-depression, high-corruption era need for hero vigilantes, which then morphed into a patriotic war-time heroism. Do Canadian superheroes come from the same place, or were they born of different social conceits and needs?

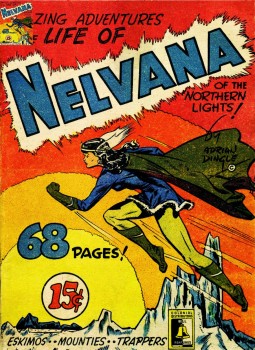

Mark: Yes, I think Canadian superheroes were born of the same stew of Depression and Second World War patriotism as their American cousins. The first wave of Canadian superheroes like Johnny Canuck, Nelvana, Brok Windsor, Thunderfist and all of those guys were created by inexperienced Canadians trying to work in the American mode when American pulps and comic books were suddenly removed from the Canadian market to save U.S. foreign exchange. Over the five or six years of WWII they evolved in different directions into things that were more distinctly Canadian (in some cases), but when the war ended, they pretty much died on the spot because they couldn’t compete with American economies of scale.

Mark: Yes, I think Canadian superheroes were born of the same stew of Depression and Second World War patriotism as their American cousins. The first wave of Canadian superheroes like Johnny Canuck, Nelvana, Brok Windsor, Thunderfist and all of those guys were created by inexperienced Canadians trying to work in the American mode when American pulps and comic books were suddenly removed from the Canadian market to save U.S. foreign exchange. Over the five or six years of WWII they evolved in different directions into things that were more distinctly Canadian (in some cases), but when the war ended, they pretty much died on the spot because they couldn’t compete with American economies of scale.

The big difference between the U.S. and Canadian traditions in superheroes (and pretty much all of speculative fiction) is that our efforts were sporadic, intermittent and didn’t form the basis of a continuing legacy for most of the 20th century. We pretty much did it, forgot it, did it again, semi-forgot it, and then did it a third time. In this generation we seem to have finally developed a sense of history about what we accomplished before and are reprinting, celebrating and reviving it. Emphasis on the “reviving”.

I know anthologists aren’t supposed to play favorites among stories (that’s for parents to do over children), but could you each gush over one of the stories in the anthology that make you proud you created this collection?

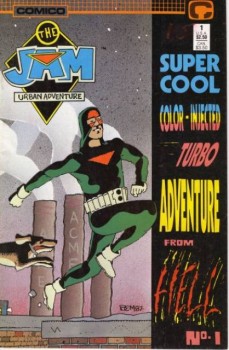

Claude: Usually, I would probably worm my way out of it, but in this case I think I can answer. I am so damn proud that this book contains the very first prose story of The Jam by Bernie Mireault. Bernie has long been one of my very favorite cartoonists (his The Jam: Super Cool Color-Injected Turbo Adventure from Hell is one of the greatest single issues of all time; probably the greatest single issue not created by Jack Kirby).

Claude: Usually, I would probably worm my way out of it, but in this case I think I can answer. I am so damn proud that this book contains the very first prose story of The Jam by Bernie Mireault. Bernie has long been one of my very favorite cartoonists (his The Jam: Super Cool Color-Injected Turbo Adventure from Hell is one of the greatest single issues of all time; probably the greatest single issue not created by Jack Kirby).

It is one of the most exciting events of my career to have co-edited the very first The Jam prose story with (and this will get incestuous) Mark Shainblum, who, as a publisher back in the 1980s, published Bernie’s earliest works, including the first comics episodes of The Jam.

Mark: Gah! I agree with Claude, it’s a Sophie’s Choice kind of question. I like different stories as representative of different styles, approaches, moods and so on, so in a way, I can honestly say they’re all my favorites. I agree with Claude about Bernie Mireault’s The Jam story.

If I never did anything else in my life, I’d get into heaven because I was Bernie Mireault’s first comic book publisher, but yeah, it was wonderful seeing a Jam story in prose in the book. And oddly, Bernie was one of the few “primarily-comics” creators who submitted a story to us. I expected more, but that’s another issue.

Without picking favorites, I will pick random examples and explain why I love them: I love Leigh Wallace’s “Bedtime for Superheroes” because it’s exactly what the title implies, the ultimate “day in the life” (or I guess “night in the life”) superhero story where, for all practical purposes, nothing happens, and yet everything happens. I love Chadwick Ginther’s “Mr. Midnight Versus Doctor Death” because it’s at once a thrilling, broad, “stomp the zombies” horror story and an up-close character study of someone in pain. I love “The Island Way” by Mary Pletsch and Dylan Blacquière because it is perhaps the ultimate story about place that Claude referred to before. I could do this for every story in the book, but I think I’ll stop there.

Wow. This has been a really cool interview, and eye-opening for me, despite having read and studied comics for a long time. Thanks so much, Claude and Mark!

Claude: Thanks, Derek!

Mark: Thanks for the interest, Derek!

The full TOC and author bios at the EDGE Publishing website. If you’d like to know more about Claude, check out claudepages.info. If you’d like to know more about Mark, check out his website at shainblum.com.

Derek Künsken writes science fiction and fantasy in Gatineau, Québec. His most recent story Flight From the Ages is in the April/May 2016 issue of Asimov’s Science Fiction.