Reflections on a Five-Sided Brain

I sat down to read Annie Jacobsen’s 2015 book The Pentagon’s Brain — subtitled An Uncensored History of DARPA, America’s Top Secret Military Research Agency — thinking I’d get a new perspective on the development of the American military-industrial complex. And a new angle on the history of science in the 1950s and 1960s and beyond. Also that I’d learn a bit about the development of the internet, and who the people were who came up with it, and why they did, and what they were thinking. I got all of that. But I also found a new angle on science fiction, and the way SF shapes the world for better or for worse.

I sat down to read Annie Jacobsen’s 2015 book The Pentagon’s Brain — subtitled An Uncensored History of DARPA, America’s Top Secret Military Research Agency — thinking I’d get a new perspective on the development of the American military-industrial complex. And a new angle on the history of science in the 1950s and 1960s and beyond. Also that I’d learn a bit about the development of the internet, and who the people were who came up with it, and why they did, and what they were thinking. I got all of that. But I also found a new angle on science fiction, and the way SF shapes the world for better or for worse.

Jacobsen’s book opens with the first test of the hydrogen bomb on Bikini Atoll in 1954, and describes the subsequent development of the Advanced Research Projects Agency (later the Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency). She follows DARPA through arguments over arms control treaties, through experiments during the Vietnam War, through the 80s and into the first Gulf War, then to projects it undertook for this century’s American wars. Of course she runs into some difficulty in these parts of the book; a lot of what DARPA does is classified. Still, Jacobsen puts together a lot of material that has previously been made public, and has information she’s gathered herself. Crucially, even where there are gaps in the record, she keeps the overall thrust of events clear.

I’d say that clarity is one of the book’s real strengths. Jacobsen’s dealing both with the labyrinthine world of intelligence and with the world of bleeding-edge science, but her book makes all this matter easily understandable. And it hints at more meaning; at what cannot yet be revealed. As well as contemplating the weird twilight between science and fiction, where one becomes another.

Stylistically the clarity of the book comes at a cost — the language is plain, even simple. And structurally the book builds itself around anecdotes, some of which have no immediate payoff. But then this isn’t a straight institutional history, describing who was in charge when, or how a specific culture was built in DARPA. Jacobsen’s more interested in deeper questions of how DARPA conceptualised science. What science did it value, and why? How did it bring the soft sciences into play, as it has by, for example, sending anthropologists to Afghanistan? How does it see science playing into warfare, and how does it see science supporting American war aims? And, crucially, how do those aims play out in peacetime and on the home front?

Stylistically the clarity of the book comes at a cost — the language is plain, even simple. And structurally the book builds itself around anecdotes, some of which have no immediate payoff. But then this isn’t a straight institutional history, describing who was in charge when, or how a specific culture was built in DARPA. Jacobsen’s more interested in deeper questions of how DARPA conceptualised science. What science did it value, and why? How did it bring the soft sciences into play, as it has by, for example, sending anthropologists to Afghanistan? How does it see science playing into warfare, and how does it see science supporting American war aims? And, crucially, how do those aims play out in peacetime and on the home front?

She quotes DARPA program managers as saying the agency is about “science fact, not science fiction.” And yet as the book goes along the two things increasingly come to converge. It’s no surprise to learn by the end that

… during the war on terror, the Pentagon began seeking ideas from science-fiction writers, most notably a civilian organization called the SIGMA group. Its founder, Dr. Arlan Andrews, says that the core idea behind forming the group was to save the world from terrorism, and to this end the SIGMA group started offering “futurism consulting” to the Pentagon and the White House. The group’s motto is “Science Fiction in the National Interest.”

Those responsible for safeguarding the nation “need to think of crazy ideas,” says Dr. Andrews, and the SIGMA group helps the Pentagon in this effort, he says. “Many of us [in SIGMA] have earned Ph.D.’s in high tech fields, and some presently hold Federal and defense industry positions.” Andrews worked as a White House science officer under President George H. W. Bush, and before that at the nation’s nuclear weapons production facility, Sandia National Laboratories, in New Mexico. Of SIGMA members he says, “Each [of us] is an accomplished science fiction author who has postulated new technologies, new problems and new societies, explaining the possible science and speculating about the effects on the human race.”

(One thing leads to another: given recent events around here I should probably note that Andrews’ novella “Flow” was nominated for a Hugo Award last year after being included on the Sad Puppy list. Anyway, per the SIGMA website, other members include Catherine Asaro, Joe Haldeman, Larry Niven, Jerry Pournelle, Bruce Sterling, and many, many others.)

(One thing leads to another: given recent events around here I should probably note that Andrews’ novella “Flow” was nominated for a Hugo Award last year after being included on the Sad Puppy list. Anyway, per the SIGMA website, other members include Catherine Asaro, Joe Haldeman, Larry Niven, Jerry Pournelle, Bruce Sterling, and many, many others.)

It sounds surreal, but it’s not surprising. We’ve seen a slow shift over the course of the book from a concern with hard physics (as with the H-bomb) to chemistry and electronics (in the Vietnam war) to the development of the internet — and from there to “network-centric warfare” and “a system of systems.” That last phrase was articulated in the 1970s, as DARPA tried to create better “command, control, and communicate” systems that would allow the American military to strike behind enemy lines. From that point, their science began to move closer to speculative fiction, in the sense not only of being speculative but of taking on aspects of the fictional. The lines between concrete fact and media imagination blurred.

In the 1980s DARPA pioneered flight simulators and battle sims. In 1990 DARPA helped manage a scripted wargame for US Central Command which used a combat simulator called SIMNET; later that year the first Gulf War took place, and Jacobsen quotes General Norman Schwarzkopf as recalling how “the movements of Iraq’s real-world ground and air forces eerily paralleled the imaginary scenario of the game.” Later in the 1990s DARPA was given the task of creating counter-agents to biological warfare after President Clinton read Richard Preston’s novel The Cobra Event, which described a near-future bioterror attack on New York City. In mid-2001 several former government officials took part in a detailed and scripted role-playing exercise called Dark Winter which involved an Iraqi terrorist attack on the US. And then there was a report about the Army’s Intelligence and Security Command, run by Lieutenant General Keith Alexander; here’s Jacobsen describing it as of 2002:

At Fort Belvoir, Alexander ran his operations out of a facility known as the Information Dominance Center, with an unusual interior design that deviated significantly from traditional military decor. The Information Dominance Center had been designed by Academy Award–winning Hollywood set designer Bran Ferren to simulate the bridge of the Starship Enterprise, from the Star Trek television and film series. There were ovoid-shaped chairs, computer stations inside highly polished chrome panels, even doors that slid open with a whooshing sound. Alexander would sit in the leather captain’s chair, positioned in the center of the command post, where he could face the Information Dominance Center’s twenty-four-foot television monitor. General Alexander loved the science-fiction genre. INSCOM staff even wondered if the general fancied himself a real-life Captain Kirk.

It’s easy to think of Dr. Strangelove when you read something like that last. But I think at least two different things, and really three, are happening over the course of these years, from the first battle sims onward. For one thing, DARPA’s focus, as Jacobsen outlines it, in part turns to the gamification of war. DARPA now gathers information about war zones both to simulate them for training exercises, and to create a virtual image through which remote operatives can pilot drones or similar machines. War meets Baudrillard.

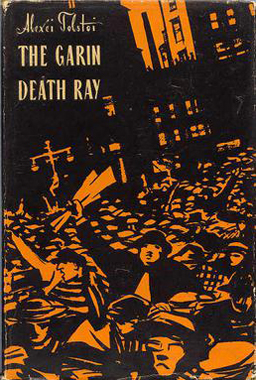

Two, science fiction’s providing the inspiration for new projects from DARPA. This is not entirely new. Fiction has always inspired science, and Jacobsen makes the point repeatedly that Charles Townes was inspired to invent the laser by Alexei Tolstoy’s 1926 science fiction novel The Garin Death Ray. But much of what DARPA is working on now seems familiar because it has long since been imagined by science fiction and comic-book writers. Soldiers in powered exoskeletons. Soldiers with scientifically enhanced physiques. Cyborgs.

Two, science fiction’s providing the inspiration for new projects from DARPA. This is not entirely new. Fiction has always inspired science, and Jacobsen makes the point repeatedly that Charles Townes was inspired to invent the laser by Alexei Tolstoy’s 1926 science fiction novel The Garin Death Ray. But much of what DARPA is working on now seems familiar because it has long since been imagined by science fiction and comic-book writers. Soldiers in powered exoskeletons. Soldiers with scientifically enhanced physiques. Cyborgs.

Three, and related to the foregoing, science fiction is providing a way to think about the increasingly advanced concepts DARPA’s dealing with. It provides a set of metaphors for dealing with ideas increasingly removed from what we understand as normal life. That’s probably especially relevant for someone like Keith Alexander (later director of the NSA and now retired), who, so far as I can see from his NSA biography, has no formal science background. I suspect for him as a fan of science fiction Star Trek becomes a way by which new technology can be articulated, can be understood. Without that set of metaphors to use as a conceptual tool, it’s difficult to grasp new technology. The American military, says Jacobsen, refused to accept a DARPA scheme to detect IEDs in Iraq through the use of trained bees essentially because the idea of bomb-detecting bugs was too far out to grasp.

But from that last point two or three other things follow in turn. All of them to do with the question of who develops the images and ideas that help to shape the way the science of the future becomes understood, and in particular becomes understood by the layman. Who’s doing this imagining?

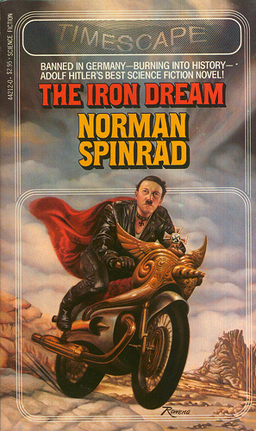

Firstly, if SF writers are creating a way of thinking about the future, and some of them are consciously working with the US government, do any of them have an agenda? I’m not talking here about politics, exactly, or not necessarily in terms of the left-right axis. I’m reminded of an article Norman Spinrad wrote in Le Monde diplomatique claiming that a group of science fiction writers led by Jerry Pournelle convinced Reagan to fund the SDI initiative, not because they believed it would be particularly useful as a nuclear shield, but because the Pentagon had more money to throw at space than NASA did and could in theory advance the infrastructure of human spaceflight. Pournelle said Spinrad got some details wrong, and notably claimed military applications were always at the forefront of SDI, but didn’t deny the attempt to use the military to develop the space program (as an aside to winning the Cold War).

Firstly, if SF writers are creating a way of thinking about the future, and some of them are consciously working with the US government, do any of them have an agenda? I’m not talking here about politics, exactly, or not necessarily in terms of the left-right axis. I’m reminded of an article Norman Spinrad wrote in Le Monde diplomatique claiming that a group of science fiction writers led by Jerry Pournelle convinced Reagan to fund the SDI initiative, not because they believed it would be particularly useful as a nuclear shield, but because the Pentagon had more money to throw at space than NASA did and could in theory advance the infrastructure of human spaceflight. Pournelle said Spinrad got some details wrong, and notably claimed military applications were always at the forefront of SDI, but didn’t deny the attempt to use the military to develop the space program (as an aside to winning the Cold War).

That’s a relatively benign way of playing with a political administration’s beliefs about science and science fiction. Now, Jacobsen makes clear that DARPA was originally founded in part out of a desire to keep the United States from being caught by surprise by an enemy’s technological superiority, as happened when the Soviets launched Sputnik. Conceived from a mid-century sense of technological positivism, the sense that the world was knowable and specifically knowable through rational hard science, DARPA was to ensure that American science and American knowing would be better than anyone else’s. SDI was a logical outgrowth of that belief: use science to defeat the nuclear threat. Ironically, one of the program’s political enemies derisively referred to the program as “Star Wars,” and that stuck. That was the way people found it easiest to think of a technology increasingly difficult to grasp. Metaphor more vivid than reality.

But what happens when someone takes advantage of the gap between metaphor and reality? This is the second point. Does DARPA, or can they, work to prevent swindles and scams taking advantage of their promised new technology? Jacobsen tells the story of Iraqi forces relying on bomb detectors that were black boxes mass-produced by a private British company. The boxes were completely useless, with no electronic or scientific component to them at all. The president of the company was eventually arrested for fraud, and an Iraqi general was arrested for taking bribes; the boxes, Jacobsen observes, were as of 2014 still in use in Iraq. The fraud took advantage of science that seems like magic. We all of us deal every day with boxes that do magic things. When given another box with a promise it can do magic, how are we to disbelieve? And so: how many schemes are out there to take advantage of us?

Thirdly, and perhaps scariest, is the question of what the technology itself will imagine. I don’t just mean what some possible AI will think of itself, though the development of AI is one of DARPA’s ongoing projects. I mean the question of whether a technology itself has an inherent logic. Given the development of the internet, is an invasive security state an inevitable outcome? Jacobsen spends much time on these questions; DARPA is constantly trying to find better and more predictive algorithms for the purpose of fighting a war and automating that war-fighting — and therefore is always trying to gather more information in order to develop those algorithms. If we’re now living in something too close to a cyberpunk dystopia for anyone’s taste, we also risk going even further in the future.

Thirdly, and perhaps scariest, is the question of what the technology itself will imagine. I don’t just mean what some possible AI will think of itself, though the development of AI is one of DARPA’s ongoing projects. I mean the question of whether a technology itself has an inherent logic. Given the development of the internet, is an invasive security state an inevitable outcome? Jacobsen spends much time on these questions; DARPA is constantly trying to find better and more predictive algorithms for the purpose of fighting a war and automating that war-fighting — and therefore is always trying to gather more information in order to develop those algorithms. If we’re now living in something too close to a cyberpunk dystopia for anyone’s taste, we also risk going even further in the future.

Reading The Pentagon’s Brain brings a sense that the world’s going to change, soon, in ways we cannot imagine; and it’s impossible to say whether those changes will be for the better or the worse. DARPA’s working on new and more advanced generations of hunter-killer robots. On miniature drones that carry explosive charges. On computer algorithms that can predict our actions, and kill any of us that look like we might be terrorists. And: it’s also working on immortality, on developing techniques by which human beings can regenerate limbs and roll back aging and even eliminate fear on a neurochemical level. Jacobsen herself concludes by pointing out that these advances are necessarily a product of the military-industrial complex — which may end up controlling whatever the scientists create.

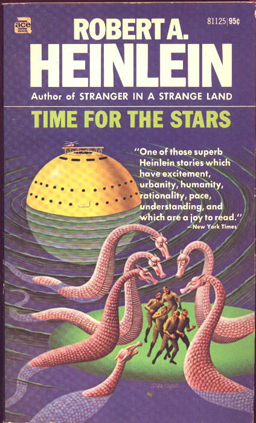

But to end on a bit of a hopeful note: reading this piece about the discovery of gravity waves (not a DARPA project, to be clear), I was struck by the reference to Heinlein’s Time For the Stars and to a society that aimed at large-scale long-term science efforts. It is true that DARPA aims big. That it does have the funding to do costly science. Maybe, however secretive it is, it will push the frontiers of knowledge. Maybe some pure research will be unclassified, maybe humanity in general will get something out of it all.

We can but hope.

Matthew David Surridge is the author of “The Word of Azrael,” from Black Gate 14. You can buy a collection of his essays for Black Gate, looking at some fantasy novels of the twenty-first century, here. You can find him on Facebook, or follow his Twitter account, Fell_Gard.