Fantasia Diary 2015, Days 15 and 16: Minuscule, Observance, Boy 7, and Big Match

I took a day off from Fantasia on Tuesday, July 28, to run some errands and buy some groceries, then returned on Wednesday to begin a kind of mini-marathon that would carry me through to the end of the festival. I saw four movies Thursday, starting at the De Sève with a wordless 3D animated French film called Minuscule, about a ladybug who falls in with a group of ants who’ve liberated a box of sugar from an abandoned picnic. After that I went to the screening room to see an Australian horror-suspense movie called Observance. Then I went back to the De Sève for the semi-science-fictional German action movie Boy 7. After getting out of that one, I made a snap decision to run across the street to the Hall Theatre to watch the Korean action-comedy Big Match. Which turned out to be one of the better calls I made all festival.

I took a day off from Fantasia on Tuesday, July 28, to run some errands and buy some groceries, then returned on Wednesday to begin a kind of mini-marathon that would carry me through to the end of the festival. I saw four movies Thursday, starting at the De Sève with a wordless 3D animated French film called Minuscule, about a ladybug who falls in with a group of ants who’ve liberated a box of sugar from an abandoned picnic. After that I went to the screening room to see an Australian horror-suspense movie called Observance. Then I went back to the De Sève for the semi-science-fictional German action movie Boy 7. After getting out of that one, I made a snap decision to run across the street to the Hall Theatre to watch the Korean action-comedy Big Match. Which turned out to be one of the better calls I made all festival.

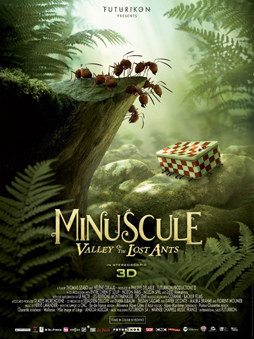

Minuscule: La vallée des fourmis perdues (Minuscule: Valley of the Lost Ants) is a feature film version of a series of five-minute animated shorts made for French TV; in English, the Minuscule shorts are subtitled The Private Life of Insects. Both TV and film version follow CGI insects with real natural backgrounds. Both (apparently; I haven’t seen the TV show) have a strong Looney Tunes feel.

Co-written and co-directed by Hélène Giraud and Thierry Szabo, Minuscule the movie follows a ladybug separated from his parents. Bullied by some flies, he joins forces with black ants who’ve found an unimaginable treasure: a tin box filled with sugar cubes, left behind by picnickers. The ladybug helps the ants get the sugar back to their queen, threatened not only by obstacles in the landscape but also by vicious red ants. But will the red ants give up the sugar, even if they succeed? In the end, the ladybug must summon his courage and push his limits to save his friends.

(I will note here that in the previous paragraph I follow the gender for the main character suggested by the IMDB synopsis. In fact none of the characters in this dialogue-free film have an obvious gender, other than the ant queens.)

(I will note here that in the previous paragraph I follow the gender for the main character suggested by the IMDB synopsis. In fact none of the characters in this dialogue-free film have an obvious gender, other than the ant queens.)

It’s a beautiful movie. The forest backgrounds are bright and bucolic; the ladybug pops out against green backgrounds. Characters are excellent designs, definitely insects but also expressive. They’ve got expressive eyes, and they act with them, communicating not just emotion but personality. It is true that individuals of a given species don’t always stand out in crowd scenes dealing with that species — but seen on their own, you know who they are and how they’ll act. The 3D here tends to emphasise the difference between the CGI and the real backgrounds. That’s more effective than it sounds, as the bugs interact reasonably well with their environment but still remain central to the eye.

The movie’s inventive plot-wise, coming up not only with different challenges for the characters but distinct tonal changes from act to act. The physics seem to change slowly over the course of the film, as things become more and more cartoony: the tin box of sugar goes through an awful lot, and it’s increasingly less likely. But because the change in physics matches the progressively cartoonish tone of the film, it all fits. By the time we get back to the black anthill and find that the ants have been stockpiling lost and abandoned items from years of human picnics, it all seems perfectly logical.

In fact, the different tones the film explores make for one of its real strengths. The opening has a kind of Disneylike feel, as we follow the young ladybug alone in the world. Then the ants come into the picture, and the struggles against the red ants, and the Looney Tunes elements become more pronounced: there’s mayhem in the forest, with a lush classical soundtrack emphasising climaxes and gag payoffs. Then the film’s last third or so seems to experiment with a number of other emotions. Awe at the ant storeroom, like the warehouse at the end of Raiders of the Lost Ark. Horror, too; a mysterious shadowed drainpipe from earlier in the film is explored, leading to one of the most original haunted-house scenes I’ve ever seen, completely with an amphibious froglike Lovecraftian beast threatening to destroy the house. (Well, okay, not actually froglike, but an actual frog. The point is: perfectly natural creatures are used dextrously to suggest the supernatural, and it’s quite successful. The scene’s a great example of using elements that follow perfectly from the premise in an unexpected but highly creative way.)

In fact, the different tones the film explores make for one of its real strengths. The opening has a kind of Disneylike feel, as we follow the young ladybug alone in the world. Then the ants come into the picture, and the struggles against the red ants, and the Looney Tunes elements become more pronounced: there’s mayhem in the forest, with a lush classical soundtrack emphasising climaxes and gag payoffs. Then the film’s last third or so seems to experiment with a number of other emotions. Awe at the ant storeroom, like the warehouse at the end of Raiders of the Lost Ark. Horror, too; a mysterious shadowed drainpipe from earlier in the film is explored, leading to one of the most original haunted-house scenes I’ve ever seen, completely with an amphibious froglike Lovecraftian beast threatening to destroy the house. (Well, okay, not actually froglike, but an actual frog. The point is: perfectly natural creatures are used dextrously to suggest the supernatural, and it’s quite successful. The scene’s a great example of using elements that follow perfectly from the premise in an unexpected but highly creative way.)

It’s very child-friendly. I’d heard it was suggested for ages seven or eight and up, but a friend of mine would take her four-year-old to a later showing with no problem. For all that the movie recalls Looney Tunes, the violence is nowhere near as extensive. There’s no sex to speak of, and bar a few minor fart jokes, I saw nothing in bad taste.

There is a touch of melancholy to the movie, though, which may sadden younger children. The ladybug never does get back to his family. That’s not really what the movie’s about. It has more to do with making friends and building a life. I suppose if you wanted to stretch it you could say that the black ants the ladybug joins up with have a structured society, as opposed to the militaristic red ants (we see their hive, and it’s all straight lines and grandiose architecture); so the movie’s about joining society and building a functioning world. But this is not a movie that hits you over the head with a moral. It’s about a ladybug’s adventures with some ants, and that’s good enough to be getting on with.

On a final note, I’ll observe that the movie ends with a dedication to Hélène Giraud’s late father, Jean, the great artist also known as Mœbius. This movie’s not that much like his stories, though perhaps the pacing’s not entirely dissimilar. But it does recall his ability to build an imaginative world, and tell a story entirely through visuals. I’ve seen a number of movies at Fantasia this year that deliberately limit their dialogue; this may, all in all, be the best — and the best-told story.

On a final note, I’ll observe that the movie ends with a dedication to Hélène Giraud’s late father, Jean, the great artist also known as Mœbius. This movie’s not that much like his stories, though perhaps the pacing’s not entirely dissimilar. But it does recall his ability to build an imaginative world, and tell a story entirely through visuals. I’ve seen a number of movies at Fantasia this year that deliberately limit their dialogue; this may, all in all, be the best — and the best-told story.

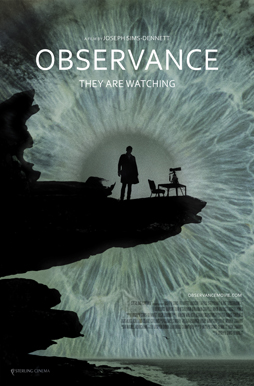

I shifted gears entirely to watch the Australian film Observance, directed by Joseph Sims-Dennett from a script by Sims-Dennett and Josh Zammit. It stars Lindsay Farris as a man named Parker, whose son recently died. Now estranged from his wife, he’s taken a job as a private investigator, lurking in an abandoned apartment to watch a woman, Tenneal (Stephanie King) across the street. The film unfolds over seven days — or so it would seem — as things grow increasingly weird. Parker only speaks to his unseen boss by telephone. Why he’s watching Tenneal isn’t made clear to him. Nor is the significance of what he sees. Tenneal has a fiancée, Bret Buchanan (Tom O’Sullivan), who comes from a privileged background; he seems to assault Tenneal, but what exactly is happening here? Events grow increasingly surreal. Parker’s body begins to break down. The apartment itself seems to turn against him. What is real and what is hallucination collapses in on itself, building to a violent climax and studied dénouement.

I shifted gears entirely to watch the Australian film Observance, directed by Joseph Sims-Dennett from a script by Sims-Dennett and Josh Zammit. It stars Lindsay Farris as a man named Parker, whose son recently died. Now estranged from his wife, he’s taken a job as a private investigator, lurking in an abandoned apartment to watch a woman, Tenneal (Stephanie King) across the street. The film unfolds over seven days — or so it would seem — as things grow increasingly weird. Parker only speaks to his unseen boss by telephone. Why he’s watching Tenneal isn’t made clear to him. Nor is the significance of what he sees. Tenneal has a fiancée, Bret Buchanan (Tom O’Sullivan), who comes from a privileged background; he seems to assault Tenneal, but what exactly is happening here? Events grow increasingly surreal. Parker’s body begins to break down. The apartment itself seems to turn against him. What is real and what is hallucination collapses in on itself, building to a violent climax and studied dénouement.

I have to make a disclaimer here: Observance is a twisty, deliberately obscure movie, and for a good chunk of its running time I misread what I thought was happening. A mention of Tenneal’s workplace led me to think that it was primarily a science-fictional thriller, and while I suspect now that there are elements of that in the film, primarily it’s dealing with older themes. In a way, this is something that’s characteristic of the film overall — it’s not always what it appears to be. The difficulty, having watched all of it, is trying to take what it actually is and connecting the dots to make a coherent picture.

I want it to make sense; I want this to be a good film. There’s a lot in it that’s obviously strong. The overall structure’s clear, and the tension’s ratcheted up effectively. The acting’s excellent, with Farris carrying the picture as the central character. He brings out the mental and physical stress building on Parker and creates a convincing portrait of a collapsed man falling further in on himself. The physical environment of the abandoned apartment’s inventive — a wall covered with pasted-up old newspapers, for example, is somehow effective at getting across the decaying nature of the place. The cinematography’s great, bringing out mood and claustrophobia. Dream sequences and occasional moments outside the apartment are necessary breaks that serve to remind us how unnatural and closed-in the place actually is. At the same time, they have reasons to exist, and create a larger world full of its own tensions. Immediate plot tensions come when Parker has to plant a bug in Tenneal’s apartment, but more profound dread is evoked as Parker meets contacts and finds that he may be involved in a larger conspiracy. And when those contacts are taken away, Parker’s plight becomes more obvious.

But is the payoff enough? As the movie goes on Parker finds stranger and stranger things, and some of the strange things he finds don’t seem to lead to anything. A jar of curious black liquid becomes a potent visual symbol, but feels underexplained. The climax slows down at odd moments, and I suspect in part that’s because on a first viewing it’s difficult to parse what exactly is happening: how all the hints are coming together.

But is the payoff enough? As the movie goes on Parker finds stranger and stranger things, and some of the strange things he finds don’t seem to lead to anything. A jar of curious black liquid becomes a potent visual symbol, but feels underexplained. The climax slows down at odd moments, and I suspect in part that’s because on a first viewing it’s difficult to parse what exactly is happening: how all the hints are coming together.

I would be interested in seeing it again to get a better sense of what was happening, which I find is a useful barometer for films that don’t immediately cohere. I think I have a basic sense of what the plot is in which Parker becomes enmeshed, and why it works out as it does. But there are also things I don’t understand. I’m reasonably sure the filmmakers have reasons for what they do. I’d need to see the film again to decide whether it’s possible for audiences to work out what those reasons are.

It’s a well-crafted film. Dream sequences in startling monochrome are both dreadful and liberating, taking us away from the apartment and the city to a natural waterside where something else terrible went on. The pacing’s note-perfect, creating a hypnotic sense of Parker struggling with unseen and perhaps unseeable forces. But specific points don’t fit together easily. The source of the film’s main horror, the elements that may be fantastic or may be hallucinated, are difficult to parse.

It may be that the film gives us enough, even if a second viewing were to leave it still mysterious. It’s perhaps enough to see the plot edge-on, from Parker’s angle, to watch a portrait of his personality under stress. But then it’s also easy to argue that that’s not enough. That events don’t have enough meaning. That Parker’s actions at the climax are unmotivated because their wellsprings are unclear.

It may be that the film gives us enough, even if a second viewing were to leave it still mysterious. It’s perhaps enough to see the plot edge-on, from Parker’s angle, to watch a portrait of his personality under stress. But then it’s also easy to argue that that’s not enough. That events don’t have enough meaning. That Parker’s actions at the climax are unmotivated because their wellsprings are unclear.

I’m left deeply unsure about the movie. Immediately after watching it I was disappointed, hoping for a few clearer hints. At this point I can see the good in it: the way the ending mirrors the beginning, the way that character and structure carry it along past specific confusing plot points. But I feel for it to be an absolute success I’d need to be clearer on what it was I watched. That may well come at a second viewing, but perhaps not. The mood is strong. But the payoff, the total coherence, is not yet there for me.

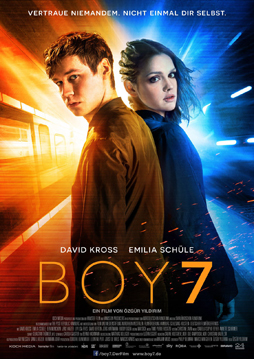

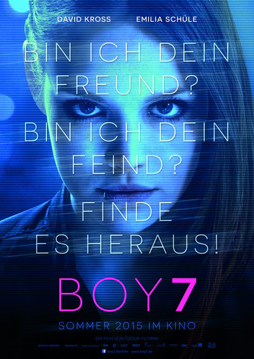

Leaving the screening room, I went back to the De Sève Theatre for a screening of Boy 7. It’s based on a YA adventure book by Dutch writer Mirjam Mous which was already adapted for the screen in a Dutch movie released earlier this year. The movie I saw was a German version of the same story, directed by Özgür Yildirim from a screenplay by Yildirim, Marco van Geffen, and Philip Delmaar — the latter two of whom wrote the screenplay for the earlier Dutch film.

Leaving the screening room, I went back to the De Sève Theatre for a screening of Boy 7. It’s based on a YA adventure book by Dutch writer Mirjam Mous which was already adapted for the screen in a Dutch movie released earlier this year. The movie I saw was a German version of the same story, directed by Özgür Yildirim from a screenplay by Yildirim, Marco van Geffen, and Philip Delmaar — the latter two of whom wrote the screenplay for the earlier Dutch film.

This movie opens in first-person, with the camera staggering through a tunnel. Our lead bursts through into a well-lit subway station, and at once the cops are after him. The movie soon shifts into a more conventional third-person framing, and we learn that we’re following a youth, Sam (David Kross), as he tries to figure out what’s happening to him. He soon finds a journal he wrote to himself, explaining what’s going on; and at the same time a girl, Lara (Emilia Schüle), who seems to be wanted by mysterious forces just as he is. They get away together, and Sam starts reading out the journal. He finds that they were escapees from an experimental facility for the rehabilitation of troubled and criminal youth, where they’d first met. Sam had learned that bad things were underway at the institute, that the teen prisoners were having their free will stripped from them. But the process didn’t entirely take with him. All these revelations set up the end of the movie, as Sam struggles against the forces trying to enslave him and his friends.

This is a plot-oriented action movie with teen heroes, which is fair enough. But the plot has problems, and by ‘plot’ I mean the connective tissue that holds the story together. Coincidence plays a large role. And the security of the evil institution holding Sam is implausibly easy to fool: apparently there are no security cameras anywhere in the building, for example.

The inventive opening of the movie’s immediately let down by what follows. The film’s dully competent, with the first-person sequence at the start probably the most formally inventive bit in it. Sam’s amnesia is an excuse for telling the story in flashbacks, creating a frame for most of the narrative without actually saying anything meaningful or adding a level of real complexity: once Sam finds the journal, the story unfolds as he reads it, starting at the beginning and moving to the end. There’s nothing particularly notable to the amnesia gimmick, and it’s basically discarded by the time the third act kicks into gear.

The inventive opening of the movie’s immediately let down by what follows. The film’s dully competent, with the first-person sequence at the start probably the most formally inventive bit in it. Sam’s amnesia is an excuse for telling the story in flashbacks, creating a frame for most of the narrative without actually saying anything meaningful or adding a level of real complexity: once Sam finds the journal, the story unfolds as he reads it, starting at the beginning and moving to the end. There’s nothing particularly notable to the amnesia gimmick, and it’s basically discarded by the time the third act kicks into gear.

Some nice moments in setting up character come to feel wasted as the character beats feed into the plot too programmatically. I can see the idea, linking plot and character, but here the plot comes to feel as though it’s the driver, with the character notes merely there to facilitate its unwinding. The worst moment comes at the height of the climax, when an elevator dumps Sam in exactly the single place where he has to be to overcome his personal trauma while also defeating the baddies. It’s far too obvious.

Faced with this, the young actors do their best. For most of the movie Kross plays Sam as though slightly stunned, confused but sympathetic; Schüle’s Lara is a tough glowering punk; and Sam’s roommate and best friend Louis (Ben Münchow) is an affable jock. It’s all very broad, but that’s what the script gives them. When character moments do arise, the actors make the best of them: Sam catching Louis masturbating one night is played by Münchow with less embarrassment than exasperation (before the plot kicks in and he has to give an explanation of how he can see his girlfriend on his cell phone when there’s no cell reception). The best moment in the movie is all Schüle’s, when she and Sam draw close and you see Lara’s prickliness fade before an almost awed tenderness and need for love.

The movie is well-shot, and does give the feel of an expansive world. There aren’t any huge set-pieces, but the ending has a satisfactory amount of running-around — if you can buy into the lack of security. And if you can accept that it’s all set up by Sam’s magic hacking powers. This is, in essence, competent commercial filmmaking. The message is so simple as to be trite (maintain your individuality, don’t let the authorities grind you down, and so on and so forth), but at least doesn’t get in the way of the story.

The movie is well-shot, and does give the feel of an expansive world. There aren’t any huge set-pieces, but the ending has a satisfactory amount of running-around — if you can buy into the lack of security. And if you can accept that it’s all set up by Sam’s magic hacking powers. This is, in essence, competent commercial filmmaking. The message is so simple as to be trite (maintain your individuality, don’t let the authorities grind you down, and so on and so forth), but at least doesn’t get in the way of the story.

The problem is that there’s also not an awful lot in the film that feels individual or distinctive. A moment here, a moment there. Some things that look interesting are only distractions: the evil boss has the same last name, Fredersen, as the master of the city in Fritz Lang’s Metropolis, but I couldn’t find any meaning to the reference. Apparently the source material did have a more overtly science-fictional setting; that might have been more interesting than what we got. It’s neither particularly good nor particularly terrible, with a final villain right out of an 80s action movie. It’s watchable. But there’s not much more to it.

From Boy 7 I ran over to the Hall Theatre to catch Big Match, a Korean action movie. I got there just as a pre-film presentation was ending; I think it was the introduction of the people behind a short film that screened before Big Match. That film was a 16-minute short called “Goldfish,” written and directed by Michael Konyves. It’s a very nice, very touching short that starts as a kind of buddy comedy, turns into a dark metaphysical inquiry into the soul, and ends with a genuinely moving testament to the power of friendship. It’s funny and unpredictable, and a very nice fantasy story.

From Boy 7 I ran over to the Hall Theatre to catch Big Match, a Korean action movie. I got there just as a pre-film presentation was ending; I think it was the introduction of the people behind a short film that screened before Big Match. That film was a 16-minute short called “Goldfish,” written and directed by Michael Konyves. It’s a very nice, very touching short that starts as a kind of buddy comedy, turns into a dark metaphysical inquiry into the soul, and ends with a genuinely moving testament to the power of friendship. It’s funny and unpredictable, and a very nice fantasy story.

And then Big Match (originally Bigmaechi). The thing I want to say about that movie is this: when I was a boy, even a teen, I’d watch TV shows like, say, The A-Team or (a little later) movies like Die Hard, and I’d wonder why they were so slow. Why didn’t the creators make a movie where every scene was people shooting stuff and punching each other and running around and explosions? Why did they bother with scenes of characters talking to each other, or, worse, mushy stuff? Apparently some people in Korea had the same thoughts I did. And they made Big Match. And it is glorious.

The first ten minutes or so are admittedly a bit slow. But once it starts, it doesn’t slow down. The world’s greatest MMA fighter is a Korean named Choi Ik-ho (Lee Jeong-jae) who got kicked out of professional soccer for being too violent (as a hockey fan I’m obliged to note that this doesn’t say much to me, but such is life). Choi’s preparing for a championship — which is suddenly canceled. Then his brother Young-ho (Lee Sung-min) goes missing. Then Choi’s arrested. And then he finds out what’s really going on. A flamboyant underworld ringmaster named Ace (Shin Ha-kyun) has captured Young-ho and set up Choi to get Choi to do what Ace wants: participate in a bizarre contest for the amusement of seven shadowy secret oligarchs. Choi’s got to break out of prison, get away from the cops, and run the obstacle course of violence and derring-do that Ace has set up, while the elite seven bet on his progress. Choi has to agree, but he starts working out ways to outmaneuver Ace, who has a flunky, Soo-kyung (K-pop star BoA), keeping an eye on him. Meanwhile, once away from the cops, Ace has Choi stage a one-man raid on a casino that happens to be Mob Headquarters — so while the police are going all-out trying to recapture Choi, so are the local gangsters.

The plot keeps snaking around, building from set-piece to set-piece. There’s a big showdown at a soccer stadium, with explosives and multiple factions and a huge crowd, and that turns out to be only the second-act climax. The movie’s 112 minutes long, but earns that running time with delirious invention and sharply-edited fight scenes and surprisingly effective comedy (which is not to say that every gag lands, but enough do that you don’t mind the occasional misfire).

The plot keeps snaking around, building from set-piece to set-piece. There’s a big showdown at a soccer stadium, with explosives and multiple factions and a huge crowd, and that turns out to be only the second-act climax. The movie’s 112 minutes long, but earns that running time with delirious invention and sharply-edited fight scenes and surprisingly effective comedy (which is not to say that every gag lands, but enough do that you don’t mind the occasional misfire).

It’s all gloriously juvenile, macho and over-the-top to the point that the idea of ‘top’ becomes purely notional. It’s a cartoon, and a great one. In the first minutes I thought Lee was playing Choi awfully broadly, but it soon became clear that he knew what he was doing — this was the tone the movie was going for. And it works. It’s the kind of movie that makes critics bring out terms like “adrenaline-packed thrill-ride” and “non-stop fun.”

If, when I was younger, I’d ever asked anyone why slow scenes were included in action shows, I might have gotten three answers. The first is that the audience needs to catch its breath every so often; so it does, and there are enough moments here where the movie moves from mainly-action to being mainly-comedy that you stay into it. The second is that there needs to be scenes that move the plot forward; here that’s done just by having the villain order the hero around by cell phone, meaning that exposition never becomes the point of a scene — we get the plot explained to us as the action moves, which works excellently. Thirdly, and most significantly, character needs to be set up or else the audience has nobody to follow through all the shoot-kick-punch scenes. But writer/director Choi Ho knows how to use action to build character, and how to make Choi a sympathetic character through the use of adventure and violence.

It’s exactly how action movies should work, in my opinion. Make the action central. For the first part of the film in particular, Choi begins a scene with a specific primary objective given him by Ace, a secondary objective to get out from under Ace’s control, a conflict coming from Ace’s orders (escape the cops, beat up the gangsters), and usually some secondary difficulty throwing a random element into things — when he starts off trying to get away from the police he’s in handcuffs, for example. So you’ve got a series of scenes where you see who Choi is from what he does to accomplish his ends despite the obstacles he faces. What better way is there to establish character?

It’s exactly how action movies should work, in my opinion. Make the action central. For the first part of the film in particular, Choi begins a scene with a specific primary objective given him by Ace, a secondary objective to get out from under Ace’s control, a conflict coming from Ace’s orders (escape the cops, beat up the gangsters), and usually some secondary difficulty throwing a random element into things — when he starts off trying to get away from the police he’s in handcuffs, for example. So you’ve got a series of scenes where you see who Choi is from what he does to accomplish his ends despite the obstacles he faces. What better way is there to establish character?

I mentioned Die Hard earlier, and there’s a similar feeling here, as Choi gets progressively beaten up through the course of the film. It’s much lighter, and Choi’s feats more superhuman, but it’s not too far away (I have not seen Die Hard: With A Vengeance, which I gather has a vaguely similar plot). It also reminds me of The Running Man, with the game-show aspect front and centre as Ace tries to run up the betting on Choi’s exploits. The film nicely captures the feel of the best moments of these movies without ever feeling like a retread.

In part that’s because of the largely successful comedy. It’s rare to get an action-comedy that pulls off both aspects, but here the two elements make for a good one-two punch (as it were), as the dramatic and comedic beats alternate. When the movie’s at its most ridiculous, the sense of comedy somehow keeps it on the rails; it feels tonally appropriate. It’s a nice trick.

In part that’s because of the largely successful comedy. It’s rare to get an action-comedy that pulls off both aspects, but here the two elements make for a good one-two punch (as it were), as the dramatic and comedic beats alternate. When the movie’s at its most ridiculous, the sense of comedy somehow keeps it on the rails; it feels tonally appropriate. It’s a nice trick.

In the end, the movie really is a blast. It’s inventive, and builds up to a final fight for Choi that’s inevitable and yet also surprising — it pays off plot points that were introduced early on, then let lie. The set-pieces are inventive, Seoul is shown off at high speed, everything’s glossy and up-tempo and exciting. Appropriately for an excellent action movie, Big Match hits everything it aims at.

(You can find links to all my 2015 Fantasia diaries here.)

Matthew David Surridge is the author of “The Word of Azrael,” from Black Gate 14. His ongoing web serial is The Fell Gard Codices. You can find him on Facebook, or follow his Twitter account, Fell_Gard.