Edgar Rice Burroughs’s Venus, Part 5: “The Wizard of Venus”

The Venus series ends not with a novel, but a novella. Consequently, this will be the shortest entry in my survey of Burroughs’s last series, but I have appended a wrap-up with my final thoughts on the Venus books as a whole.

The Venus series ends not with a novel, but a novella. Consequently, this will be the shortest entry in my survey of Burroughs’s last series, but I have appended a wrap-up with my final thoughts on the Venus books as a whole.

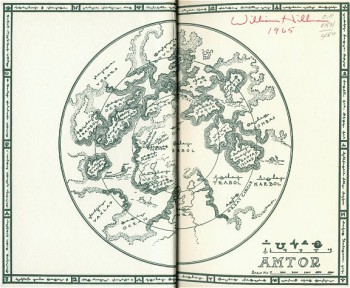

Our Saga: The adventures of one Mr. Carson Napier, former stuntman and amateur rocketeer, who tries to get to Mars and ends up on Venus, a.k.a Amtor, instead. There he discovers a lush jungle planet of bizarre creatures and humanoids who have uncovered the secret of longevity. The planet is caught in a battle between the country of Vepaja and the tyrannical Thorists. Carson finds time during his adventuring to fall for Duare, forbidden daughter of a Vepajan king. Carson’s story covers three novels, a volume of connected novellas, and an orphaned novella.

Previous Installments: Pirates of Venus (1932), Lost on Venus (1933), Carson of Venus (1938), Escape on Venus (1941).

Today’s Installment: “The Wizard of Venus” (1964)

The Backstory

Edgar Rice Burroughs’s experiment of writing the previous Venus book as four linked novellas succeeded — commercially, at least — so he forged ahead with a new story in 1941 to start a second quartet. But no magazine purchased “The Wizard of Venus.” ERB moved on to the second story, which he started on 2 December 1941 in his home in Hawaii.

You can see where this is headed.

Burroughs was an eyewitness to the attack on Pearl Harbor on 7 December 1941: he and his son Hulbert saw the events unfold from the tennis court of their home, at first believing it was a military exercise. Six days later, Burroughs joined the Allied effort as a war correspondent. He would eventually return home to Hawaii, but he would never return to Venus.

“The Wizard of Venus” first saw print in 1964, fourteen years after its author’s death, in the omnibus Tales of Three Planets. In 1970, the novella was paired with a short novel found in the author’s files, a contemporary adventure with a eugenics sub-theme titled Pirate Blood, for its Ace publication. All editions since have used this same pairing, sometimes under the title The Wizard of Venus and Pirate Blood, which sounds like one weird school of magic.

The Story

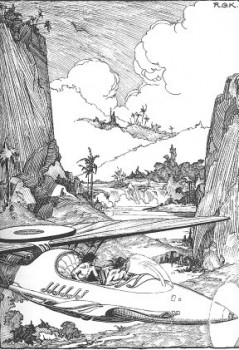

Carson Napier is at last back in his favorite country of Korva, where he is a prince (tanjong). He and his friend Ero Shan build a new flying machine (anotar) and go exploring. However, weather forces them down in a kingdom under the control of a “wizard” named Morgas. Morgas keeps the locals in fear with his power to turn their kidnapped relatives into zaldars (the Amtorian version of pigs). Carson deduces this is only a trick; if Morgas can convince people that their loved ones might be hidden among their own zaldars, they won’t eat them and Morgas can seize their abandoned livestock while protecting his own.

The two heroes set out to rescue a woman named Vanaja from Morgas so they can retrieve the anotar and their weapons from her family, who seized them when they landed. They reach Morgas’s castle and discover the man is a charlatan who uses simple stage magic and hypnotism to convince people he has sorcerous powers. Carson fights back with his own mental abilities to rescue not only Vanaja, but all the people who live in fear of the false wizard.

The Positives

This short piece is a galactic-sized improvement over Escape on Venus. If Burroughs had completed the other novellas in this intended book with the same flair, this might have been one of the high points of the Amtor adventures. The writing and pacing are strong, the situations fun, and the flashes of satire effective without excess.

Best of all, the funny Edgar Rice Burroughs has returned! From the first pages, the witty style and sly sarcasm that added an extra pinch of enjoyment to many of ERB’s early adventure stories roars back. It starts in the first paragraph of the story proper (after the standard introduction from the fictional Burroughs), where Carson calls himself “the prize incompetent of two worlds,” and it hums through the rest of the story. It’s wonderful to see ERB hurling out gems like this:

At that, Noola laughed: I think a writer of horror stories would have called it a hollow laugh. I don’t know what a hollow laugh is. I have never known. I should describe Noola’s laugh as a graveyard laugh; which doesn’t make much more sense than the other, but is more shivery.

There are some clever dialogue exchanges as well, particularly one where Carson repeatedly calls Morgas a “jackass,” then makes some snide comment about jackasses in high places in his world, and finally apologizes to all jackasses everywhere because they actually are intelligent animals … and the same can’t be said about Morgas.

There are some clever dialogue exchanges as well, particularly one where Carson repeatedly calls Morgas a “jackass,” then makes some snide comment about jackasses in high places in his world, and finally apologizes to all jackasses everywhere because they actually are intelligent animals … and the same can’t be said about Morgas.

Carson Napier finally achieves the right balance as a hero: he still can’t fight off hordes of enemies, but he displays exceptional cleverness and ingenuity in dealing with Morgas and saving those the false wizard has enslaved. Carson engages in sharp banter with his adversaries, and not in the smug jerk fashion of Escape on Venus. He seems like a real hero at last when he seizes the initiative with old-fashioned chivalry. (He makes the direct comparison between him and Ero Shan and Arthurian knights.)

Carson at last uses his telepathic abilities within a story. These powers have been mentioned since Pirates of Venus as Carson’s method of communicating his adventures back to Earth, but he never used them in this adventuring. This failure to use a major power for any reason except sending the fictional Edgar Rice Burroughs information for a new book has always rankled with me. But at last, Carson pulls out the mind mojo where it counts: saving his life and the lives of others.

Morgas is a fun villain for a novella. He could never stretch out for a full book — he isn’t powerful enough — but in this short space he gives the right combination of danger and silliness. The powerless villains of Escape on Venus were just blowhards, but Morgas is a funny blowhard, and well-written, and that makes all the difference.

Ero San has a good buddy relationship with Carson. He doesn’t do much, but he helps out with Carson’s turn toward the humorous side. It’s no Butch and Sundance pairing, but it keeps the story breezing along.

The Negatives

The Negatives

No, not another anotar! Not another forced landing in a strange new country suffering under a tyranny!

Although it is good to see Carson’s mind powers put to use, it does come screaming out of nowhere and leaves the reader wondering why he didn’t do this any time before.

Carson’s “Jedi mind tricks” point toward the only serious flaws in “The Wizard of Venus”: there isn’t much action, and Carson never seems in serious danger. He uses his mental power to facilely manipulate events until he has saved everyone. It is impressive, however, how much ERB covers up this deficiency with plenty of amusing writing and strong characterizations.

Oh, that extra novel Pirate Blood included in the volume? Don’t bother. Really, do not bother.

Craziest bit of Burroughsian Writing: “How much an optimist I am, you may readily judge when I admit that I have been hopefully waiting for years for seven spades, vulnerable, doubled, and redoubled. I might also add that at such a time my partner and I have one game to our opponents’ none, we having previously set them nineteen hundred; and are playing for a cent a point — notwithstanding the fact that I never play for more than a tenth. That, my friends, is optimism.”

Most Triumphantly Stupid Carson Napier Moment: Forgetting he had telepathic powers during all his time on Venus until this story.

Best Monster: Nothing new here except for the zaldar.

Most Uncomfortable Moment for the Modern Reader: The moment the anotar has to make a forced landing, everyone will think, “Not this again!”

Casrson Napier, Political Satirist: Remarking on the robotic response of viewers to one of Morgas’s feats of “magic”: “It was as spontaneous and unrehearsed as a drafting of a president for a third term.”

Should ERB have continued the series? Yeah, why not? This is a promising beginning, even if it seems that the next three novellas would have repeated the same “anotar crashes in a new place” pattern. However, we shall never know.

Series Wrap-Up

Perhaps somewhere in ERB fandom exist people who think that the Venus series is not the worst one that the author wrote. They are entitled to their opinion, even though it is wrong. (Kidding, kidding.)

But I will concede that, having read the whole series in a short period, it isn’t as horrible as detractors often make it out to be. Lost on Venus and Carson of Venus deliver some surprises, and any ERB reader should give them a try. “The Wizard of Venus” is a pleasant upswing at the end, when it looked as if the series was depleted.

However, when the Venus series is bad, it is truly awful. That one of the worst books, the plotless slog of Pirates of Venus, starts it off means that few readers will ever want to go any farther. Although the next two books have strong elements to them, neither is great: Lost on Venus is sometimes downright uncomfortable, although the eugenics aspects will interest readers who take the historical view of it; and Escape on Venus is almost unreadable and close to its author’s worst work.

The Venus books lack a “big picture” to stitch them together, and that damages it the most as an overall series. Carson Napier is the only through-line, and he’s a weak and passive hero burdened with mental limitations and a boring love interest. The ideas that ERB cultivates about the planet at the beginning — the Thorists and the battle for Vepaja’s freedom — vanish after only one book, and each subsequent book conjures a new civilization and adventure that add nothing to Venus as a coherent location. It is easy to forget that the stories are taking place on Venus. Barsoom is a real place in the Mars novels; Amtor is just a bunch a cities where a powered glider keeps crashing.

The Venus books lack a “big picture” to stitch them together, and that damages it the most as an overall series. Carson Napier is the only through-line, and he’s a weak and passive hero burdened with mental limitations and a boring love interest. The ideas that ERB cultivates about the planet at the beginning — the Thorists and the battle for Vepaja’s freedom — vanish after only one book, and each subsequent book conjures a new civilization and adventure that add nothing to Venus as a coherent location. It is easy to forget that the stories are taking place on Venus. Barsoom is a real place in the Mars novels; Amtor is just a bunch a cities where a powered glider keeps crashing.

If Burroughs had moved the focus away from Carson Napier in the later books, the same way he changed protagonists in the Barsoom series, it might have freed him up and stopped the damning repetition. Carson isn’t a fellow who can sustain four novels; the amusement of him as screw-up wears out fast. It isn’t until “The Wizard of Venus” that Burroughs discovers the balance to make him both funny and appealing as a hero. The rest of the time, he feels like the comic relief instead of the lead (except in Escape on Venus where he’s just a jerk.)

Burroughs was in a writing slump during most of the time he wrote these novels, and it shows. The prose often feels loggy and bored. Only “The Wizard of Venus” feels like it has his zip of the ‘teens, and it still contains little action. Burroughs still has his satire, but he’s shooting all over the horizon with different ideas and never nails anything. The Zani-Nazis of Carson of Venus are the strongest piece of satire, but they don’t turn out to be effective villains in the long run, which hurts the comparison to the Nazis.

The Venus novel progression captures all of Burroughs’s late-period writing in miniature. In the early 1930s he seems stuck in the same mode, repeating early concepts but without much passion. As the decade moves on, he tries a few new concepts, tosses in some particularly barbed personal ideas he probably should have left alone, but still struggles to make it work. At the end of the decade, desperate to keep selling, he stumbles into a low point. And then, finally, at the end of his career, he experiences a sudden revival. “The Wizard of Venus” along with Burroughs’s last few novels, Tarzan and the “Foreign Legion” and I Am a Barbarian, show the old man still had it in him.

The Venus books are only for the most serious Burroughs enthusiasts. Casual readers may wish to check out Lost on Venus for the standard adventure material and the eugenics craziness — they’ve been warned about that — but they won’t get much else from Amtor. I am as hardcore an ERB lover as you will find, and getting through all these stories in a two-month period was a test even for me.

But we’ll always have Havatoo and its, ahem, perfect society.

My ranking of the series, from best to worst:

Lost on Venus

“The Wizard of Venus”

Carson of Venus

Pirates of Venus

Escape on Venus

Ryan Harvey is one of the original bloggers for Black Gate, starting in 2008. He received the Writers of the Future Award for his short story “An Acolyte of Black Spires,” and his stories “The Sorrowless Thief” and “Stand at Dubun-Geb” are available in Black Gate online fiction. A further Ahn-Tarqa adventure, “Farewell to Tyrn”, is currently available as an e-book. Ryan lives in Los Angeles. Occasionally, people ask him to talk about Edgar Rice Burroughs or Godzilla in interviews.