“We Belong Dead”: Bride of Frankenstein

I will be one of the Black Gate team present at the World Fantasy Convention this weekend, so if you are there as well, just look for the guy who appears lost. (I’ve never been to one of the big conventions before.)

Two weeks ago I discussed the key Hammer Horror film for Halloween, Dracula (1958). It would be a grave omission not to discuss my key Universal Horror film for Halloween—especially since this year is that movie’s seventy-fifth anniversary.

Two weeks ago I discussed the key Hammer Horror film for Halloween, Dracula (1958). It would be a grave omission not to discuss my key Universal Horror film for Halloween—especially since this year is that movie’s seventy-fifth anniversary.

This is going to be a “strolling” review, in which I walk through an entire film and simply point at things. It’s a good sort of October stroll, I think.

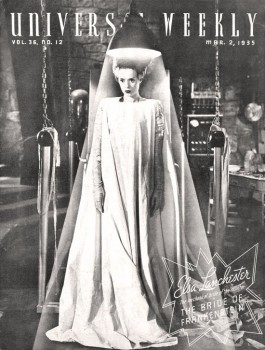

Three-quarters of a century ago, on April 22nd, Universal Pictures released the long-rumored, delayed, and awaited sequel to their 1931 smash hit adaptation of Frankenstein by Mary Shelley: Bride of Frankenstein. The world of Gothic film has never been the same. Bride is the highest achievement of the Universal Horror series, the best film ever from director James Whale, and a defining moment in the cinema of the fantastic, weird, and grotesque. Every viewing of the film is an unfettered joy and a voyage through the dark imagination.

(Promotional materials advertise the film as The Bride of Frankenstein, but the actual on-screen title eliminates the definite article, and I’m a martinet about these things.)

Universal in the 1930s built their House of Horrors on the twin success of Dracula and Frankenstein in 1931. A later successful double feature of the two would create the Universal Horrors of the 1940s. And it was the director of Frankenstein, British import James Whale, one of many theatrical directors who were given film directing jobs in the new world of the “Talkies,” that the studio pegged as their great hope not only for horror, but to put the studio on a competitive level with MGM. Whale wasn’t only a sure hand with horror movies like Frankenstein, The Old Dark House (1932), and The Invisible Man (1933), but also produced successful stylish comedies, musicals, and murder mysteries for the studio.

Whale’s reputation was considerable in his prime during the 1930s, but it wasn’t until the rise of film studies and the appreciation for genre movies in the 1970s that he started to change into a major auteur. Whale, unfortunately, wasn’t around to witness this: he committed suicide in his Pacific Palisades home (the suburb where I grew up, by the way) in 1957. Bride of Frankenstein is now recognized as his masterpiece, the film where he brought together his visual style, sense for regional and campy comedy, love of the bizarre, and dramatic instincts in a wonderful entertainment meld.

Whale had resisted the idea of doing a sequel to Frankenstein when the studio pressured him to produce a follow-up to one of their biggest hits. But once he had established himself with other movies, and Carl Laemmle Jr. promised him full creative control, he attacked the sequel and made—well, let’s see what he made.

Whale had resisted the idea of doing a sequel to Frankenstein when the studio pressured him to produce a follow-up to one of their biggest hits. But once he had established himself with other movies, and Carl Laemmle Jr. promised him full creative control, he attacked the sequel and made—well, let’s see what he made.

Bride of Frankenstein is an odd film in many ways, which is one of the reasons it stands like such a titan in its genre. Where the first film was done in stark designs, with almost no musical score, and with a balance of “standard” Hollywood drama scenes along with the strange horror, the sequel is baroque and lush (photographed by John Mescall), filled with one of the greatest early sound film scores (by Franz Waxman), and drenched in weirdness without a single scene that might be termed “normal.”

Its structure is perhaps the oddest thing about it, since it violates most standards of a how a screenplay is supposed to be put together. Many authors had a hand in crafting it (playwright William J. Hurlbut has final screen credit, with Hurlbut and John L. Balderston sharing an “adaptation” credit), but the final result is a movie divided into four distinct parts:

Prologue: The Dark and Stormy Night of Mary Shelley

Part I: The Temptation of Dr. Henry Frankenstein by the Devil, Dr. Septimus Pretorius

Part II: The Monster, And How the World Spurned, Embraced, and Spurned Him Again

Part III: The Bride, And How She Came into the World and How That World Was Destroyed

Those three parts are not the conventional thee acts of the “Three Act Structure” now used and overused and overused some more in discussing script structure. They function almost as segments of a movie serial, independent units that don’t so much build to each other as they reflect each other from their surfaces.

Prologue: Mary Shelley

“It’s a perfect night for mystery and horror. The air itself is filled with monsters.”

According to Elsa Lanchester, the actress cast as both author Mary Shelley and the titular Bride, James Whale wanted this unusual prologue to show “how very pretty people can have very wicked thoughts.” Good explanation. But there’s even more going in this bizarre opening, which in a chronological sense, is inexplicable. Occurring clearly in the early nineteenth-century, when Mary Shelley was married to Percy Selley, the prologue then tells a story taking place in some mixture of the early 1930s (look at Henry Frankenstein’s suits) and a crossbred locale of Victorian England and the second German Empire. But this is a fantasy, of course, and the purpose here is a clash between the sophisticates of the Great Romantic Poets and their mad dreams. It also puts the creation of the Frankenstein Myth and the birth of Gothic and Romantic literature in their proper context, allowing the viewer to see Bride of Frankenstein as a cinematic century-later flowering of all of what came earlier.

According to Elsa Lanchester, the actress cast as both author Mary Shelley and the titular Bride, James Whale wanted this unusual prologue to show “how very pretty people can have very wicked thoughts.” Good explanation. But there’s even more going in this bizarre opening, which in a chronological sense, is inexplicable. Occurring clearly in the early nineteenth-century, when Mary Shelley was married to Percy Selley, the prologue then tells a story taking place in some mixture of the early 1930s (look at Henry Frankenstein’s suits) and a crossbred locale of Victorian England and the second German Empire. But this is a fantasy, of course, and the purpose here is a clash between the sophisticates of the Great Romantic Poets and their mad dreams. It also puts the creation of the Frankenstein Myth and the birth of Gothic and Romantic literature in their proper context, allowing the viewer to see Bride of Frankenstein as a cinematic century-later flowering of all of what came earlier.

It looks great, too. Just from the aesthetic POV, the prologue opens the film drenched in beauty and otherworldliness. Lanchester is lovely and hypnotic in her part, a seemingly demure lady with a creative power that will stun the world. The way she is shown physically tugged between Byron and Shelley, mirroring how the Bride is torn between Dr. Frankenstein and Dr. Pretorius later in the film, is magnificent.

As the prologue finishes (having served its main narrative function of providing a flashback to Frankenstein), Mary Shelley promises more of the story, and the camera rushes back from the grand drawing room, taking the audience deep into the new tale….

Part I: The Temptation

“To a new world of gods and monsters!”

The Monster makes a short appearance at the beginning of Part I, emerging from the watery ruins under the mill and giving audiences their first view of Jack Pierce’s adapted “scarred” make-up for Boris Karloff. The monster murders two peasants and gets a screeching retreat from Frankenstein’s “blimey!” housekeeper Minnie (Una O’Connor). The monster won’t appear again until Part II, almost of third of the way into the film.

The rest of this section, as my invented title suggests, is how Henry Frankenstein, recovering from the tragedy of the last film and hoping to find wedded bliss with Elisabeth (seventeen-year-old Valerie Hobson, replacing Mae Clark from the first movie), is tempted back to his scientific experiments by the devilish figure of Dr. Pretorius (Ernest Thesiger).

James Whale was deft with British comedy, and Bride of Frankenstein is often a very funny movie. But the humor of the film isn’t “comic relief,” so often seen in other horror films from the period, but is woven into the nature of the world and its characters. The black humor of James Whale never comes through stronger than in this first segment of Bride of Frankenstein, where actors Una O’Connor and Ernest Thesiger run rampant. O’Connor, who played a similar part in The Invisible Man, was a favorite of Whale’s and provides the most outrageous campy and stagy humor in the movie. And it’s amazing how well she works in this context; O’Connor is a genuinely hilarious actress to watch.

Enter Ernest Thesiger as Dr. Septimus Pretorius, the film’s most ingenious original creation. Pretorius is the lynchpin of the film, its villain and motivator. Thesiger’s character combines theatrical comedy flourishes with Mephistophelean menace—he even makes an overt comparison between himself and the Devil when he introduces one of the miniature creatures he has grown (a stunning visual sequence from the master of The Invisible Man’s effects, John P. Fulton). However, Pretorius isn’t only a creation of the performer: the use of editing and bizarre skull-like lighting make him a central visual presence in the movie. Pretorius is almost as much a monstrous creation of the filmmaking mad scientists as the monster Pretorius tries to convince Frankenstein to make.

Part II: The Monster

“Alone—bad. Friend, good!”

Henry wavers on whether to follow Pretorius’s call to create a masterpiece combining their talents, and with that the movie switches to a pastoral scene and re-introduces the Monster.

Karloff’s pantomime performance in Frankenstein is a marvel, but his return to the role four years later may be the best acting in his career. (I think there’s a good case to be made for The Mummy and The Body Snatcher, however.) According to the actor’s daughter, he originally objected to the Monster speaking in the new film because it would weaken the effectiveness of the character, but “…he was wrong. History has proven him wrong.” The Monster is at his most human and destructive in this film, and throughout this sequence he swings wildly between both.

The pacing here is frantic at first, a hint of the mania that will erupt in the finale. The Monster thrashes through the countryside, terrifying people as he simply tries to survive. This sends a classic enraged mob to pursue and capture him to the accompaniment of a woe-filled march on the soundtrack. The Monster breaks out of captivity immediately, ripping apart doors, hurling people around, and showing once again that James Whale had no problem having the feature creature murder children.

But then the film takes a breath, and its a sweet, beautiful one… all too short. The Monster finds refuge with a blind Hermit (O. P Heggie, Whale’s first and only choice for the part) who accepts the lost creature as he is. This sequence, like a number of others sprinkled throughout the movie, comes directly from Shelley’s novel. It is with the hermit that the Monster learns to speak, and Karloff shows how expressive he could make only a few words.

Like so many other things in Bride of Frankenstein, this is a bizarre sequence and a strange filmmaking choice. It has no connection to any of the “plot” of the film, aside from allowing the Monster to speak in later scenes. No other scenes intercut with it. It should stop the film dead in its tracks with maudlin treacle. Yet it doesn’t. Instead, it’s unforgettable—the purest moment of kindness for the Frankenstein Monster in his career at Universal. Both Heggie and Karloff play with such sincerity that no false no false appear. The audience is also torn apart because they know that this happy state of affairs cannot last.

Like so many other things in Bride of Frankenstein, this is a bizarre sequence and a strange filmmaking choice. It has no connection to any of the “plot” of the film, aside from allowing the Monster to speak in later scenes. No other scenes intercut with it. It should stop the film dead in its tracks with maudlin treacle. Yet it doesn’t. Instead, it’s unforgettable—the purest moment of kindness for the Frankenstein Monster in his career at Universal. Both Heggie and Karloff play with such sincerity that no false no false appear. The audience is also torn apart because they know that this happy state of affairs cannot last.

And indeed, John Carradine (in an uncredited part as a hunter) comes in and spoils it all. The loss of the Monster’s only true friend drives him underground, and his hate leaves him easy prey for Dr. Pretorius.

Part II concludes in the most appropriate place: a crypt. The monster’s trip through the world of the living has brought pain, failure, fire. The Monster returns to the dead, where he came from originally. “Love dead. Hate living,” he defiantly tells Dr. Pretorius, whom he finds in the crypt. The bad doctor is celebrating there with a bottle of wine and toasting to a human skull, and he is not the least bit put out to find a murderous killer made from dead bodies standing beside him. The Monster has discovered the devil (accompanied to a piece of music that composer Franz Waxman titled “Danse Macabre”) among the creatures like him, and the Devil has the most tempting offer: Let me play God and create for you. Just for you.

Dr. Pretorius has found his soulmate, and will produce for him his soulmate.

“You make man, like me?”

“No, woman. Friend for you.”

Part III: The Bride

“We belong dead!”

(I was thinking of titling this part, “Why Do We Even Have That Lever?”, but I opted for a more serious tone.)

Dr. Pretorius’s proposal to the monster brings down the curtain on the second act, and the pieces are now in place to force Henry Frankenstein to create the female monster. After gently requesting that Henry carry through the procedure (“Must do it!”), Pretorius has the Monster kidnap Elisabeth to force the reluctant doctor’s hand.

And so the action shifts to the tower laboratory on the bluff, crammed with the best Kenneth Strickfaden electrical equipment to give the audience a stunning light show for the finale. The laboratory set, a massive expansion on the one in the 1931 film, is the quintessential “mad scientist playground,” one of the indelible cultural gifts of the Universal Horror movies

And so the action shifts to the tower laboratory on the bluff, crammed with the best Kenneth Strickfaden electrical equipment to give the audience a stunning light show for the finale. The laboratory set, a massive expansion on the one in the 1931 film, is the quintessential “mad scientist playground,” one of the indelible cultural gifts of the Universal Horror movies

As Dr. Frankenstein announces that the new heart is beating, a slow drum tap in the orchestra starts up to parallel it. So begins an almost uninterrupted ten-minute piece of music from Franz Waxman, “The Creation,” that becomes the operatic accompaniment of the astonishing, near-hysterical finale of Bride of Frankenstein. This is a sustained piece of crafted from the brilliance of performances, photography, design, editing, and of course, music. When I think of the term “pure cinema,” a full confluence of all the pieces of the art, this is one of segments that immediately appears in my head. Although it isn’t clear what Pretorius and Frankenstein are doing with all these broom handle switches and electrical currents, it doesn’t matter: it looks amazing and creates its own electricity.

The title character finally makes her appearance, in her famous Nefrititi-inspired lightning hairdo. Elsa Lanchester only has a few minutes of screen time in the part, but she does a remarkable amount with it. The Bride supposedly has a completely fresh, vat-grown brain inside the corpse of the nineteen-year-old girl, and Lanchester gives the newborn creature a sense of confusion and wonder with her bird-like movements. She also shows a draw toward Henry Frankenstein as a father figure, but refuses in no uncertain terms the man her “father” has picked for a husband.

And this is where the Switch You Must Not Pull comes into play. Elisabeth makes an unexplained escape from captivity to pull Henry away with her before the Monster slams down the castle (another great model effect from Fulton) on himself, Pretorius, and the hissing Bride. Waxman’s music rises in a final triumph using his elegant “Bride Theme,” and the Greatest Horror Movie of the 1930s comes to a close.

Thank you for your patronage, and please check around your immediate seating area before exiting the theater.

I’ll see everybody at World Fantasy! Have a wonderful Halloween and goodnight!

very interesting this review and the series on Marvel The monster of Frankenstein by William Patrick Maynard, for me is much more interesting the creature of Victor Frankenstein than Dracula, in the Universal film Dracula is a kind of smart man seducing damsels while the monster of Frankenstein is much more, the same with the novels Dracula is a kind of hunt of the vampire while the novel Frankenstein is much more tragical and even psychological and characters oriented…

[…] of Frankenstein (1935) You can read me go on and on about this masterpiece here. I don’t have much more to say about the greatest of Universal’s classic monster films, so […]