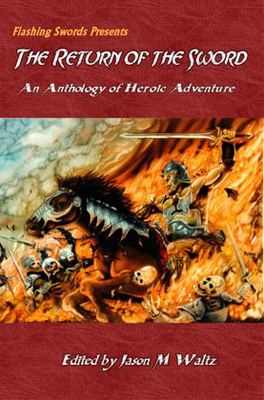

Fiction Review: The Return of the Sword

By Ryan Harvey

Copyright © 2008 by New Epoch Press. All rights Reserved.

Edited by Jason M. Waltz

Flashing Swords Press, 2008, 329 pages, Trade Paperback ($16.50), E-Book ($7.50)

If you have a craving for sword-and-sorcery, straight-up no chaser, then you’ll find it in The Return of the Sword, the new anthology from Flashing Swords Press. Editor Jason M. Waltz has gathered together nineteen short stories, seventeen making their first appearance, of heroic fantasy. The key word here is “heroic”; with a few interesting exceptions, the offerings on display make no delay hurling their courageous warriors onto the front lines to let them carry out their bloody business to our old-fashioned delight. There are fiends to slay, damsels to rescues, and titanic battles to win, and even if the stories aren’t all equals, none of them wastes the readers’ time getting to the juicy red meat.

The “Editor’s Pick” for best story is “The Last Scream of Carnage” by Phil Emery, which delves into avant-garde stylization for its dark fantasy tale about the grim Carnage-Lord and his foray into Darkmaw. It’s an intriguing piece, but some readers may dislike the rhythmic shortened lines and dabblings in free verse. However, my personal choice for the best story would be a split vote between “What Heroes Leave Behind” by Nicholas Ian Hawkins and “An Uneasy Truce in Ulam-Bator” by Allan B. Lloyd and William Clunie. Hawkins’s story has the strongest characterization in the anthology. He delves into a realistic portrayal of an aging hero who gives himself purpose once more when asked to investigate the strange happenings in the ruins of Ustrien. The writing duo of Lloyd and Clunie provide the most lighthearted romp you could want from sword-and-sorcery without diverting into outright parody. Their story of a mage and barbarian who become accidentally linked together like a fantasy version of The Defiant Ones makes an enjoyable switch from the grim earnestness that appears in many of the other stories in The Return of the Sword.

However, if you want savagery, turn straight to Steve Goble’s “The Mask Oath.” It is one of the most intense and violent selections, but what sets it apart is that it takes what appears to be a standard revenge tale and then up-ends readers’ expectations about its avenger’s true motives. Following close behind in quality is the excellent work from Christopher Heath, “Claimed by Birthright.” The mood here leans more toward high fantasy than sword-and-sorcery, but Heath executes some clever slight-of-hand in his tale of a duel set up between a barbarian clan-lord and a sorcerer. Another duel story, “The Hand That Holds the Crown” by Nathan Meyer (a reprint from Amazing Journeys Magazine) balances out Heath’s story with its sheer ferocity. There isn’t much more to the piece than the action of half-brothers in battle for a crown, but Meyer is a seasoned pro whose writing strikes with the same force as the duelers it describes.

A reader hungry to mainline pure sword-and-sorcery adventure should flip to Angeline Hawkes’s “Lair of the Cherufe.” Barbarian hero Kabar goes forth to rescue a kidnapped princess — from sacrifice to a lava monster, no less — and generous portions of creative action ensue. It’s quite tasty; if you want the heroic goods delivered, this is the place to start. In a similar vein is “Mountain Scarab” by Jeff Stewart, which travels over the well-trod ground of “the duel for the chieftainship,” but it’s excellently told and Stewart details the tribal life of its characters in an interesting way. There’s further barbarian adventure in “Deep in the Land of the Ice and Snow” by Ty Johnson, but beyond its surface action is an irreligious attitude that perfectly captures the popular sword-and-sorcery concept of the hero who won’t let anything, not even the gods, restrain him.

Grand warfare is at the core of a number of the stories. Bill Ward’s “The Wyrd of War” abandons dialogue completely for a description of an enormous dark fantasy battle. It works as a prolonged prose-poem, and anyone wanting to immerse him or herself in feverish madness will get a thrill from Ward’s headlong action. Jeff Draper provides straightforward combat mayhem in “The Battle of Raven Kill,” where a single warrior defends a bridge against an attacking force that swarms against him. The writing in this tale of a last stand is a rush from beginning to end. Military action also takes center stage in Bruce Durham’s “Valley of Bones,” which features an attack by a rampaging mammoth skeleton. Seriously, what other recommendation do you need than that?

In a few places, editor Waltz’s choices step outside the expected boundaries of heroic adventure, with mixed results. “The Dawn Tree” by S. C. Bryce, a tale of Dermanassian the desert elf, emphasizes characterization and the fantastic over explicit action and adventure. Robert Rhodes’s “To Be a Man” (a reprint from the magazine Aoife’s Kiss) is the story most likely to divide readers. The tone is anti-heroic and sexuality comes to the fore. Regardless of what readers may think of the content, the story’s brazenness makes it one of the collection’s most unusual. Although James Enge’s “The Red Worm’s Way” doesn’t stray far beyond the tone of the anthology, it does feature a hero — Morlock, who has appeared in other of the author’s stories — using his brains instead of brawn to defend a corpse from a gruesome overnight onslaught. “Altar of the Moon,” the opening story in the anthology, peers into the part of heroic fantasy that readers seldom experience: what happens to a magical weapon after its prophetic role has ended. Think of it as a stinger that plays after the credits of a movie have finished — stay after and you might learn something new.

Some of the stories suffer from space limitations, and dropping a few longer pieces into the mix of shorts would have given the writers valuable stretching room; sword-and-sorcery is a genre ideally suited to the novella format. “To Destroy All Flesh” by Michael Ehart feels too much like part of a series than a story that stands on its own, which make the fine world-building cramped. “Guardian of Rage” by Thomas M. McKay barrels along with energy as it follows its hero Jack Sprytle through the sewers with a demon box and a rescued little girl, but it ultimately lacks context and room to breathe. It would have worked excellently as a novella. The same can also be said for David Pitchford’s intriguing but too compressed “Fatefist at Torkas Nahl.”

In addition to fiction, The Return of the Sword also contains a short primer on writing from E. E. Knight, “Storytelling.” It contains helpful pointers for the fantasy author, but writers of any genre could pick up a few tips here. Knight rolls out his advice with a humorous, jovial voice similar to the tone Steven King uses in On Writing: A Memoir of the Craft. My only complaint about Knight’s essay is its placement in the middle of the anthology, when it would feel more organic separated at the end as an appendix. Of course, readers don’t have to approach the stories in the editor’s order, but the aesthete in me finds this placement of nonfiction in the middle of fiction awkward.

As a bonus, the anthology closes with a reprint from the golden era of the pulps. “Red Hands” isn’t fantasy but an historical adventure about Cossacks in the late seventeenth century. Author Harold Lamb had an enormous influence on Conan creator Robert E. Howard, so any sword-and-sorcery reader will appreciate the inclusion of his work. If Lamb’s story overshadows some of the newer works in The Return of the Sword, well, that’s why it’s designated as a “classic.”

5 thoughts on “Fiction Review: The Return of the Sword”