Monster Mash-up: Elizabeth Hand’s Pandora’s Bride

February is Women in Horror Month, and with that in mind I’d like to look at an interesting oddity. In 2005, Dark Horse Books, a then-recently launched imprint of Dark Horse Comics, announced they’d be publishing a set of tie-in novels. These novels wouldn’t tie into the big modern-day entertainment franchises that Dark Horse Comics was known for working with, though. Instead, they’d each present the further adventures of one of the famous Universal Studios horror characters. I happened to stumble across one a little while ago: Pandora’s Bride by Elizabeth Hand. Hand is a fine writer and I was happy to find that she’d taken her assignment here and run with it. Ostensibly, the book’s about the adventures of “the Bride of Frankenstein,” but Hand’s cleverly and amusingly told a story about several other remarkable film characters as well, playing with some of the great works of German Expressionist film and of Fritz Lang in particular.

February is Women in Horror Month, and with that in mind I’d like to look at an interesting oddity. In 2005, Dark Horse Books, a then-recently launched imprint of Dark Horse Comics, announced they’d be publishing a set of tie-in novels. These novels wouldn’t tie into the big modern-day entertainment franchises that Dark Horse Comics was known for working with, though. Instead, they’d each present the further adventures of one of the famous Universal Studios horror characters. I happened to stumble across one a little while ago: Pandora’s Bride by Elizabeth Hand. Hand is a fine writer and I was happy to find that she’d taken her assignment here and run with it. Ostensibly, the book’s about the adventures of “the Bride of Frankenstein,” but Hand’s cleverly and amusingly told a story about several other remarkable film characters as well, playing with some of the great works of German Expressionist film and of Fritz Lang in particular.

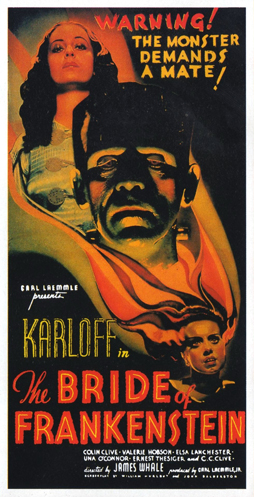

Her main character, though, is the Bride — is there any other film character that’s made such an impact, become such an icon, with so little actual screen time? The Bride doesn’t appear until the final few minutes of the 1935 movie named for her; and then almost all she does is point and scream. Yet nearly everyone knows who she is. Her image is unmistakeable. Obviously, that’s a function of striking visual design. It may help that Elsa Lanchester, who played both the Bride and Mary Shelley (in a prologue to the film’s main action), ended up settling in to a career filled mostly with character roles and few other starring appearances. But for whatever reason, the Bride exists as perhaps the most literally iconic of movie roles: an image, with no character arc attached.

So Hand’s first task in this novel would be to find a story for the Bride. A prolific novelist and short story writer, Hand’s won all sorts of awards: a Nebula for her short story “Echo,” International Horror Guild Awards in 2001 for Best Long Form work and in 2002 for Best Intermediate Form, two World Fantasy Awards for Best Novella and one for Best Collection, and both a Tiptree Award and a Mythopoeic Award for her 1994 novel Waking the Moon. She’s an excellent writer, and specifically a horror writer, as well as a veteran of tie-in fiction — in addition to writing a number of movie novelisations, she’s produced four Boba Fett children’s books for Lucasfilm. (And perhaps Boba Fett before the prequel films and the Extended Universe would have been the only other character remotely close to the purely-iconic nature of the Bride; but then Fett had appeared in a cartoon segment in a TV special even before his first appearance in Empire, as well as newspaper comic strips.) All told, Hand was a good choice for the job.

She begins the novel right where the original Bride of Frankenstein movie ended: an explosion in the laboratory where the Bride comes to life. She survives and she’s not the only one. She rescues her co-creator, Doctor Pretorius, and the two return to Pretorius’s home. There, we’re introduced to some of Pretorius’s other creations, half-formed monsters called the Children of Cain, as well as to his valet, a sleepwalker named Cesare. But they’re soon found out and their odd household must flee in the guise of a travelling circus; exposed by a vengeful Henry Frankenstein, the Bride, now having chosen the name Pandora for herself, must flee on to Berlin, where strange things are afoot. It seems an inventor named Rotwang has created a mechanical woman, not wholly unlike Pandora herself, who is spreading unrest among the working class. Meanwhile, the city’s terrorised by a child murderer with a fondness for whistling airs from Grieg. It all comes to a spectacular conclusion underneath Berlin, a kind of replay of the ending of the movie, with a confrontation between Pandora, her intended mate, Henry Frankenstein, and various other entities — a structural mirroring that reveals how far Pandora’s come.

She begins the novel right where the original Bride of Frankenstein movie ended: an explosion in the laboratory where the Bride comes to life. She survives and she’s not the only one. She rescues her co-creator, Doctor Pretorius, and the two return to Pretorius’s home. There, we’re introduced to some of Pretorius’s other creations, half-formed monsters called the Children of Cain, as well as to his valet, a sleepwalker named Cesare. But they’re soon found out and their odd household must flee in the guise of a travelling circus; exposed by a vengeful Henry Frankenstein, the Bride, now having chosen the name Pandora for herself, must flee on to Berlin, where strange things are afoot. It seems an inventor named Rotwang has created a mechanical woman, not wholly unlike Pandora herself, who is spreading unrest among the working class. Meanwhile, the city’s terrorised by a child murderer with a fondness for whistling airs from Grieg. It all comes to a spectacular conclusion underneath Berlin, a kind of replay of the ending of the movie, with a confrontation between Pandora, her intended mate, Henry Frankenstein, and various other entities — a structural mirroring that reveals how far Pandora’s come.

So the story’s a kind of bildungsroman; in this case a story about a woman — a necessarily unconventional woman — making her way in a man’s world and striving to keep from being defined solely by men and by her relationships to men. Which is appropriate, I think, given that the character before this book was known only as a bride. Hand gives her strength of will, determination, and intelligence; all this might be enough, in a patriarchal society, for her to be cast in the role of ‘monster’ even without the nature of her origin. As it is, it all seems to dovetail nicely: her choice of ‘Pandora’ as a name is a defiant, knowing act, but it also glances back to the subtitle of Shelley’s original novel, “The Modern Prometheus”: Pandora and her box (or jar, as the myths have it) were sent to humanity as punishment for Prometheus’s theft of fire. Hand plays knowingly with Greek myth and mythic imagery throughout the book, complete with a final descent into the underworld. It’s not heavy-handed, but makes an amusing counterpart to the main action.

The myth and the gender issues fuse seamlessly. Much of the symbolic power of Frankenstein (book or film) comes from the implied cosmic wrongness of a man usurping the female role of making life; so here the gender politics become a reversal of a reversal, a mirror of a mirror. One might further mention that The Bride of Frankenstein is also held to gain some thematic power from director James Whale’s homosexuality — something relevant here, as among the people Pandora encounters are young Englishmen Wystan and Christopher, presumably a reference to Wystan Hugh Auden and Christopher Isherwood. All these things work together with a charming lightness of touch. The book’s nominally horror, I suppose, but the tone is increasingly arch, again perhaps echoing the complexity of tone of the original film. It’s quick and light and also thoughtful, a thinking person’s pulp fiction.

The myth and the gender issues fuse seamlessly. Much of the symbolic power of Frankenstein (book or film) comes from the implied cosmic wrongness of a man usurping the female role of making life; so here the gender politics become a reversal of a reversal, a mirror of a mirror. One might further mention that The Bride of Frankenstein is also held to gain some thematic power from director James Whale’s homosexuality — something relevant here, as among the people Pandora encounters are young Englishmen Wystan and Christopher, presumably a reference to Wystan Hugh Auden and Christopher Isherwood. All these things work together with a charming lightness of touch. The book’s nominally horror, I suppose, but the tone is increasingly arch, again perhaps echoing the complexity of tone of the original film. It’s quick and light and also thoughtful, a thinking person’s pulp fiction.

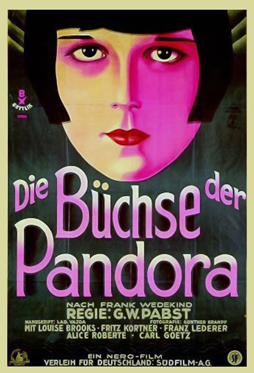

You can see that in the supporting cast Pandora encounters. A monster to conventional society, Pandora naturally comes to live on the margins and meet equally marginal figures; but ‘marginal’ here may be better understood as ‘liminal,’ figures on the threshold to something else. At any rate, the practical point is that Hand brings in figures from other films, and the novel becomes a witty mash-up of German Expressionist film. I caught references to The Cabinet of Doctor Caligari and M and Metropolis and The Blue Angel and, perhaps most pointed, to a Louise Brooks movie called Die Büchse der Pandora, or Pandora’s Box (Brooks, like Brigitte Helm of Metropolis, was originally considered for the role of the Bride). And in all this, Hand does something quite difficult: she avoids having all these things become a series of gratuitous cameos. Each figure from each film has a reason for being in the story. They advance and shape a plot that reflects the ongoing themes of Pandora’s new life.

(Interestingly, the way Hand uses these elements helps nail down certain things about the setting. The original film of The Bride of Frankenstein is confusing as far as that goes; the opening prologue casts the main story as a tale being told by Mary Shelley in 1818, but the rest of the film seems to be set much later. Hand fixes her story firmly in Germany in the 20s, in the interwar era of cabarets and confusion.)

The book’s not flawless. Notably, Hand’s prose, while still more than serviceable, isn’t as fluid as in some of her other novels. It’s always competent, but occasionally unsubtle. That’s not a fatal flaw — if this is a kind of pulp fiction, pulpy bluntness fits right in — but it does make the book occasionally feel flat. Notably, the first half of the book sometimes seems disjointed, even slow. Pandora doesn’t have much of a driving desire during those first hundred pages, beyond simply finding a way to live in the world.

The book’s not flawless. Notably, Hand’s prose, while still more than serviceable, isn’t as fluid as in some of her other novels. It’s always competent, but occasionally unsubtle. That’s not a fatal flaw — if this is a kind of pulp fiction, pulpy bluntness fits right in — but it does make the book occasionally feel flat. Notably, the first half of the book sometimes seems disjointed, even slow. Pandora doesn’t have much of a driving desire during those first hundred pages, beyond simply finding a way to live in the world.

But once she arrives in Berlin, things really pick up and the book moves from strength to strength over its second half. There’s an almost joyous sense of play here, an intoxicating feel (at least for me, familiar with most of the movies Hand refers to). If it’s pulp, it mimics some of the best pulp in being almost blissfully unconcerned with being good or bad writing, and concerning itself simply with telling a wild, adventurous story. Hand’s got an ability to string together images in a symbolic pattern that’s uncommon if not nonexistent in typical pulp fiction, but she also has a sense of storytelling craft. The result is a fun, charming, occasionally passionate, and surprisingly thoughtful novel. It’s more than you’d expect from a book about “The Bride of Frankenstein.” It’s arguably better, and cleverer, than a tie-in project has any business being.

Matthew David Surridge is the author of “The Word of Azrael,” from Black Gate 14. His ongoing web serial is The Fell Gard Codices. You can find him on Facebook, or follow his Twitter account, Fell_Gard.

[…] Monster Mash Up: Elizabeth Hand’s Pandoras Bride […]

[…] Leonora Carrington’s The Hearing Trumpet, Elizabeth Hand’s Bride of Frankenstein tie-in novel Pandora’s Bride, a collection of short stories by Violet Paget AKA Vernon Lee, Amos Tutuola’s The Palm-Wine […]

I found this article very insightful. Pandora’s Bride was not easy to track down a copy of (and not cheap) but I’m glad I did. Your words helped contextualize a lot of the narrative and also alerted me to some of the film references I might have missed. Most of them were familiar to me but I hadn’t seen Pandora’s Box or The Blue Angel. I watched them before starting Hand’s novel and I’m glad I did–they were incredible!