Thor and the Fear of Fantasy

As a good Shakespearean, Kenneth Branagh understands fantasy. I think the movie Thor succeeds mostly because of what he as a director brings to the film, and what he’s able to get out of his cast. What’s missing seems to be what the script doesn’t give him — a larger world, memorable supporting characters, and a willingness to engage with the matter of fantasy.

As a good Shakespearean, Kenneth Branagh understands fantasy. I think the movie Thor succeeds mostly because of what he as a director brings to the film, and what he’s able to get out of his cast. What’s missing seems to be what the script doesn’t give him — a larger world, memorable supporting characters, and a willingness to engage with the matter of fantasy.

The tale’s simple enough. Following an incursion of evil frost giants into the realm of Asgard, Thor, son of Asgard’s ruler Odin, leads a retaliatory raid against the giants; because this endangers a fragile peace between the realms, Odin exiles Thor to earth, stripping him of his power. Thor and his magic warhammer Mjolnir materialise in New Mexico, where he’s befriended by rogue cosmologists, deals with agents of the superspy organisation S.H.I.E.L.D., and struggles against the plots of his brother Loki. Thor ultimately has to regain his power to return to Asgard to save all the worlds from Loki’s schemes.

It’s an enjoyable adventure movie. The set-pieces are well staged, the design of the visuals are distinctive, and the actors sell the material by consistently hitting the right balance between the grounded and the larger-than-life. But the script of the movie struggles to fit the mythic material at the core of the story into standard superhero movie structures.

Charlie Jane Anders sums up the typical superhero movie plot here: “Clueless loser. Gets superpowers. Shirks his destiny. Faces his destiny. Meets super-baddy. Loses. Faces his darkest hour. Fights super-baddy again. Wins. The end. Yay!” Thor’s basic premise forces it to start differently; at the beginning of Thor the main character’s not a loser, though he is clueless about a number of things. But the familar plot structures soon manifest, so though Thor begins the movie as a god possessing godly powers, the movie takes those powers away from him so he can earn them back. As soon as he performs an act of self-sacrifice, his godly nature returns.

Charlie Jane Anders sums up the typical superhero movie plot here: “Clueless loser. Gets superpowers. Shirks his destiny. Faces his destiny. Meets super-baddy. Loses. Faces his darkest hour. Fights super-baddy again. Wins. The end. Yay!” Thor’s basic premise forces it to start differently; at the beginning of Thor the main character’s not a loser, though he is clueless about a number of things. But the familar plot structures soon manifest, so though Thor begins the movie as a god possessing godly powers, the movie takes those powers away from him so he can earn them back. As soon as he performs an act of self-sacrifice, his godly nature returns.

Of course big Hollywood movies live off of the familiar. And given the amount of money sunk into the making of a major film, that’s understandable. But the use of familiar plot structures feels here like a way of domesticating the unfamiliar; a way of making the threateningly unpredictable more mundane. I think that’s a particular problem here because the comic Thor at its best feeds on the energy and colour of high fantasy. Take that away, and I think you risk diminishing the vitality of the whole project.

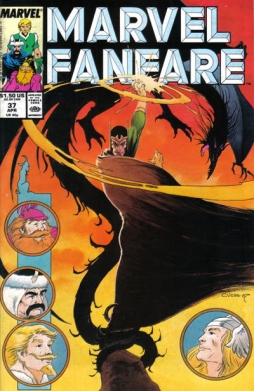

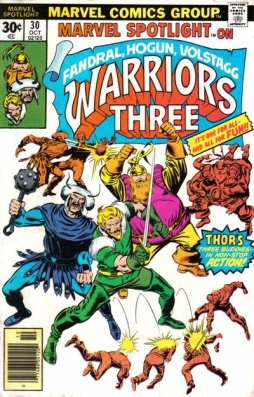

Look at the movie’s supporting cast, perhaps its weakest element. The Warriors Three are wonderful characters in the comics, roughly the Three Musketeers as Norse Gods. In the movie, though, they’re sadly colourless. Hogun isn’t grim enough, Fandral isn’t dashing enough, and Volstagg is nowhere near voluminous enough — or cowardly enough, or funny enough. And Sif, a Norse fertility-goddess reimagined by artist Jack Kirby as a black-haired warrior-woman, is sidelined by the movie in favour of the always-less-interesting Jane Foster.

At the same time, Asgard overall is poorly imagined, and the movie suffers for it. There’s no sense of the Asgardians as a people, as a culture or a community, meaning that Odin’s role as their king or Thor’s role as their prince feels meaningless. Indeed, Asgard seems oddly underpopulated. It looks nice, with breathtaking camera moves past eye-popping designs, but where are the people?

At the same time, Asgard overall is poorly imagined, and the movie suffers for it. There’s no sense of the Asgardians as a people, as a culture or a community, meaning that Odin’s role as their king or Thor’s role as their prince feels meaningless. Indeed, Asgard seems oddly underpopulated. It looks nice, with breathtaking camera moves past eye-popping designs, but where are the people?

Frankly, the movie doesn’t want to deal with them. They’re not actually gods, the film suggests; they’re powerful aliens who were worshipped by the Norsemen of a thousand years ago after they saved the world from the giants, another race of aliens. This is a bad idea from recent Marvel comics — I don’t know that the notion was around before Alex Ross’ tedious out-of-continuity miniseries Earth X — which is disturbingly reminiscent of an old Star Trek episode (“Who Mourns for Adonais,” if you want to be precise). I think the idea actually works in Star Trek, which is supposed to be science fiction. But here it seems like a fantasy mileu, and a fantasy story, is being forced into a science-fictional form.

Part of the reason seems to be a desire on the part of Marvel to set up the upcoming Avengers movie. Characters like Iron Man and Captain America are “grounded,” they reason, more science-fictional in nature, so therefore Thor needs to be made science-fictional as well. I’m skeptical. To me, one of the appeals of super-hero comics in general, and team books in particular, is the way in which different genres can mix together. So you can have a team with, say, a god, a man in high-tech armour, a super-soldier, a telepathic martial-artist raised by alien priests, a couple of mutants, a robot (or “synthezoid“), and a guy who happens to be really good with a bow and arrows — and somehow it makes sense (the bowman, as it happens, appears in Thor; again, following a recent Marvel re-imagining, it seems to me they’ve misunderstood him totally, taking a character whose defining trait is an inability to take orders gracefully and forcing him into a role within a military chain of command). Perhaps what’s most admirable about the super-hero story, when done well, is its imaginative wildness; the complete lack of bounds on the imagination, the sense of a universe large enough to include any kind of story. But Marvel seems here to be backing away from that.

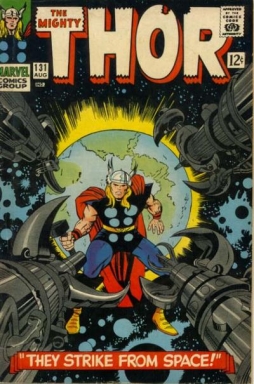

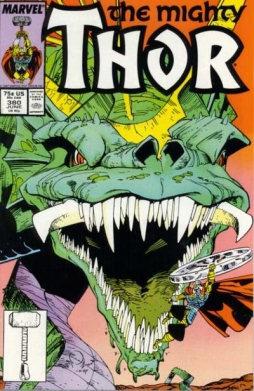

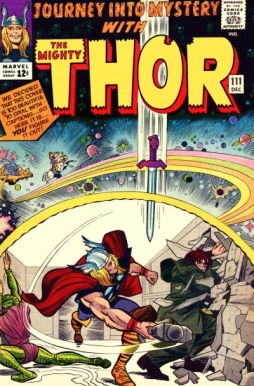

Certainly Thor the comic at its best distinctively fused fantasy with science fiction. Kirby had Thor encounter aliens (the Colonizers of Rigel, for example), a super-evolved human geneticist called The High Evolutionary, and even a living planet. Walt Simonson, whose work on the book is commonly agreed to be the best since Kirby’s, continued that theme by having Thor meet an alien hero named Beta Ray Bill, who was leading his people on an exodus out of the Burning Galaxy — which turned out to be Burning because it was the workshop where Surtur the flame giant was forging a sword with which to destroy the universe. The mix of high fantasy and epic science fiction not only made the book a highly individual tone, but gave it power and scope even in a genre known for wild high concepts.

Certainly Thor the comic at its best distinctively fused fantasy with science fiction. Kirby had Thor encounter aliens (the Colonizers of Rigel, for example), a super-evolved human geneticist called The High Evolutionary, and even a living planet. Walt Simonson, whose work on the book is commonly agreed to be the best since Kirby’s, continued that theme by having Thor meet an alien hero named Beta Ray Bill, who was leading his people on an exodus out of the Burning Galaxy — which turned out to be Burning because it was the workshop where Surtur the flame giant was forging a sword with which to destroy the universe. The mix of high fantasy and epic science fiction not only made the book a highly individual tone, but gave it power and scope even in a genre known for wild high concepts.

Enjoyable as the movie is, there’s little of that wildness. There is, if anything, a movement away from the challenging. Which seems limiting when much of the matter of the story comes out of fantasy and myth, and so by its nature aspires toward a mythic tone.

It’s been said that Thor’s difficult to sell as a comic. High sales on a recent relaunch of the book were credited to the fact that there’d been no regular Thor book for four years before the relaunch. I wonder, though, if it’s not the case that Thor is difficult for a lot of creators to get their heads around. In general, it seems that the current wave of creators at Marvel is more comfortable with science-fiction stories than fantasy stories, and perhaps more comfortable with crime and espionage stories than either. And Thor is a quintessentially fantastic work.

Both of the book’s two classic runs, by Jack Kirby and by Simonson, were products of very distinctive sensibilities, and indeed of very personal relations to the source material (in the case of the Kirby run, with scripter Stan Lee desperately trying to keep up). Simonson was conscious of his Norse roots, and tried to bring a real sense of the Viking myths into the book. And Kirby, one of the most powerful creators in the history of the medium, worked into Thor his own fascinations with myth, evolution, and power; not only one of his greatest works, Kirby’s Thor also leads directly into his Fourth World cycle of stories, which began with the words “There came a time when the old gods died!” — said “old gods” being fairly clearly shown to be the Marvel Asgardians.

Both of the book’s two classic runs, by Jack Kirby and by Simonson, were products of very distinctive sensibilities, and indeed of very personal relations to the source material (in the case of the Kirby run, with scripter Stan Lee desperately trying to keep up). Simonson was conscious of his Norse roots, and tried to bring a real sense of the Viking myths into the book. And Kirby, one of the most powerful creators in the history of the medium, worked into Thor his own fascinations with myth, evolution, and power; not only one of his greatest works, Kirby’s Thor also leads directly into his Fourth World cycle of stories, which began with the words “There came a time when the old gods died!” — said “old gods” being fairly clearly shown to be the Marvel Asgardians.

I think that to the extent the Thor movie works — and I feel it does work, a fair bit — it’s because Kenneth Branagh was able to create a solid imagining of his own of the characters and background of the story. There’s much Kirby in his Asgard, and in the character designs. But they work as film creations in their own right. The effects shots of Asgard are unreal, but thoughtfully so — they’re the right kind of surreal to create the sense of a location that’s both unearthly and beautiful. I may want more of a sense of the people who live in the place, but as a place it’s distinctive and fantastic.

When the movie succeeds, it is, in fact, mythic. Odin appears early in the film on horseback; the film artfully doesn’t draw attention to the fact that the horse has eight legs. The backstory that it reveals, of ancient wars between gods and giants, of a prince raised in the house of his people’s enemy without knowing his true identity, has the timeless feel of myth.

And the main cast inhabit their roles perfectly, playing the mythic and the human at once. There’s a clarity and purpose to every scene, and every character moment. I’ve read some reviews saying that Loki was puzzling; if anything, I felt the film erred on the side of making him too simple. He begins as a mischief-maker, and develops into a greater villain as events unfold. By nature a schemer, he becomes more so as the story grows. I’ve also seen people say that Chris Hemsworth’s Thor changes too quickly; but it seems clear to me that his first failure at reclaiming his hammer is a world-changing event for him. I think his picking himself up and developing to the point where he’s prepared to sacrifice himself for others is obvious enough, and well-dramatised enough, that nothing more is needed than what Branagh gives us.

And the main cast inhabit their roles perfectly, playing the mythic and the human at once. There’s a clarity and purpose to every scene, and every character moment. I’ve read some reviews saying that Loki was puzzling; if anything, I felt the film erred on the side of making him too simple. He begins as a mischief-maker, and develops into a greater villain as events unfold. By nature a schemer, he becomes more so as the story grows. I’ve also seen people say that Chris Hemsworth’s Thor changes too quickly; but it seems clear to me that his first failure at reclaiming his hammer is a world-changing event for him. I think his picking himself up and developing to the point where he’s prepared to sacrifice himself for others is obvious enough, and well-dramatised enough, that nothing more is needed than what Branagh gives us.

At its heart, Branagh’s Thor is about a family dynamic. But Branagh understands that this is at heart a fantasy film; so what makes the film work is not the fathers-and-sons story in and of itself, but the way the fantastic is fused with the family matter. The basic emotions of generational conflicts and sibling rivalry and struggles for inheritance lend meaning to a fairy-tale-like magical sleep, to an exile in the mundane world, to a hammer that belongs only to the worthy; and those fantastic elements themselves are what shape the story, what make it distinctive and memorable. And mythic.

Which is to say that Thor works because Branagh uses the fantasy elements to broaden and extend the themes he’s interested in. It is, therefore, a fantasy story. I think where the movie backs away from the fantasy, it tends to fail; it imposes a limit on itself, a limit on its imagination and daring. It fails when, as a fantasy, it is afraid to explore the matter that it is working with.

Clearly, though, the movie does have great fantasy film moments. My favourite comes about not as a function of visual effects or costume design, but through Chris Hemsworth’s acting. It happens when Thor, determined to go out into the desert and reclaim Mjolnir, strides into a pet shop. “I need a horse,” he tells the surprised store-keeper.

Clearly, though, the movie does have great fantasy film moments. My favourite comes about not as a function of visual effects or costume design, but through Chris Hemsworth’s acting. It happens when Thor, determined to go out into the desert and reclaim Mjolnir, strides into a pet shop. “I need a horse,” he tells the surprised store-keeper.

“We don’t sell those,” the man says. “This is a pet store. We sell dogs, cats, birds …”

“Very well,” says Thor. “Give me one of those large enough to ride.”

It’s funny; but it ought to be just a fish-out-of-water gag. I found Hemsworth delivered with it just the right mix of casualness and conviction that it created the sense of a whole world, natural to the character, filled with battle-cats and war-hounds and giant eagles. It’s a small moment that builds a setting without showing it. It’s an example of the movie getting things right; of how Branagh and his cast can build moments of wonder out of seemingly simple lines. It’s an example of why Thor succeeds — because, for all the market-driven forces working against it, those moments of fantasy insist on making themselves felt.

Matthew David Surridge is the author of “The Word of Azrael,” from Black Gate 14. His new ongoing web serial is The Fell Gard Codices. You can find him on facebook, or follow his Twitter account, Fell_Gard.

Another great post, MDS.

I agree that the weak point of the (largely great) THOR movie was the Warriors Three. Not because they were badly cast (they weren’t), but because they weren’t embraced as the original characters they are supposed to be. A Volstagg who isn’t hugely obese simply isn’t Volstagg (the character is itself an ode to Shakespeare’s Falstaff, legendary fat guy). Fandral didn’t get a chance to be dashing, and Hogun didn’t get a chance to be grim. However, my thinking is that (hopefully) these characters will be given more screen time in the future–and will begin to heave closer to the source material. I mean Volstagg can always GET fat, right?

I do have one issue with your post, though: EARTH X was fantastic! So were its sequels.

Overall, I’m satisfied with THOR and X-MEN FIRST CLASS as the latest Marvel Comics movie triumphs. I am, however, more interested in NEW ideas these days—ones where I DON’T already know the story going in. This is why I couldn’t bring myself to see GREEN LANTERN this weekend, even though it looks visually stunning in previews and trailers. I know the story in and out. Show me something NEW.

My fear is that since Marvel as firmly established itself as a big player in the film industry, they will keep repeating and repeating their classic stories over and over into the next decade and beyond. Comics has a bad habit of repeating itself anyway, and now they’re doing it on film. So, as excited as I am by some comic-based movies, I’m far more excited by original movie ideas that bring something entirely fresh to the medium.

If I want comics, I’ll read COMICS.

Thank you, I agree with literally every word of this essay. I liked the film but it feels frustratingly mundane next to the potent mythology/space opera mixture of the comics, especially after spending a couple of months leading up the film’s release absorbing the Kirby and Simonson runs in large chunks thanks to the two Thor Omnibuses Marvel released over the past year.

I believe the “Asgardians are really aliens” concept doesn’t originate with Earth X, but is something that has been advanced in the comics for a good while by nonbelieving characters to rationalize the existence of the Asgardians and the other godly pantheons. That is, the readers know the Asgardians are actually the real Norse gods, with their golden apples and all, but the characters within the stories aren’t sure. I think the film would have been more advised to do it like that, maybe having Jane and Stellan Skarsgaard trying to come to grips with Thor in their particular ways, as opposed to having Thor himself lay it all out with his wishy-washy “magic and science are the same thing, which you of course know because you’ve read Arthur C. Clarke” exposition.

John: Thanks for the good words!

Yeah, the actors playing the Warriors Three did have some flashes — I noticed Fandral laughing during the opening fight, which was the right general approach. I guess I’m a bit worried about how much they can pick it up, though; maybe it’s just me, but I always felt that Hogun, for example, was a guy who should freak you out just by looking at him. Since the Warriors Three are now established, can they actually be brushed up into coolness? Maybe. We’ll see.

I admit it’s been a while since I read Earth X, and I never did get around to the sequels. Honestly, I just remember a lot of exposition, and a very slow story. I did read it all in one go, which may have affected my judgment. Then again, I also didn’t particularly like the ideas about the Marvel Universe in the book — not that they were invalid, just that they didn’t particularly connect with me. So that could play a part as well.

I still haven’t seen FIRST CLASS; I’m looking forward to it. I generally agree with wanting to see new stuff in film, but … there’s an exception in that if filmmakers actually do an adaptation of a specific story, intelligently revised to make a good transition to film, maybe that’d be interesting. I’m saying that because the most (only?) interesting thing to me about the new WOLVERINE movie they’re planning is the fact that they’re going to do it as an adaptation of the Claremont/Miller miniseries. If they can figure out how to bring the stylistic flash of the book’s storytelling into film, then that could be pretty great. We’ll see.

Andy: Thanks! I think you’re right that it’s a rationalisation other Marvel characters came up with to explain the presence of Thor, but I don’t think the other heroes ever bought into it. Though I guess there were lots of times even in the Silver Age when somebody would think something along the lines of “Who does he think *he* is?”

For what it’s worth, there’s a Marvel wiki which suggests that it’s fairly directly from Earth X:

http://marvel.wikia.com/Asgardians

(Scroll down to “Asgardians of Earth-9997”)

I definitely think you’re right that the film would’ve been better if they’d allowed some ambiguity to it.

I had the opposite reaction to EARTH X. I loved how it took 40 years of Marvel Continuity and wrapped it all up in a great, big package that literally EXPLAINED EVERYTHING…while telling an engaging story of a truly weird world. The concept that most enaged me is that of the Earth as a huge “egg” gestating a baby Celestial inside it. That the radiation from this was mainly responsible for the birth of super-powered invidivuals and humanoid races of the Marvel U. For me, it took decades of unconnected and often contradictory chaos and tied it up in a nice sci-fi package. (With awesome artwork.)

“In general, it seems that the current wave of creators at Marvel is more comfortable with science-fiction stories than fantasy stories, and perhaps more comfortable with crime and espionage stories than either”.

An intriguing point. That trend goes as far back as Frank Miller. In Daredevil Chronicles#1, he noted that he did not read much fantasy literature, preferring crime fiction such as Richard Stark, Spillane, Chandler, etc. In an article in Wizard#25 and an interview with Hart D. Fisher in Hero Illustrated, he said much the same. Brian Michael Bendis noted he had much the same mindset about Daredevil, feeling him as more of a pulp hero than the more cosmic properties such as the Fantastic Four. Miller noted that he preferred to keep his Daredevil stories relatively grounded.

(I find it interesting that Miller’s run on Daredevil started two years after Star Wars came out. One would have thought that Star Wars would cause a move toward more cosmic fare. However, despite its huge success, Star Wars did not lead to the decline of the police procedural/noir/Western derived adventure film that we see today. In other words, after Star Wars came out, two more Dirty Harry films came out and all of the Death Wish films came out. Since Harry Potter’s first film, none of these franchises have produced sequels or reboots.)

However, although these writers prefer crime fiction, in fact the more cosmic properties such as the Fantastic Four, the X-Men, etc. have tended to have higher box office grosses than the relatively grounded properties. In point of fact, Daredevil’s film, stands as considered a bit of a disappointment, and that film definitely followed the Miller feel for several points.

In fact, the new “truism” has started that costumed heroes without great powers will not do well, with the exception of the recent Zorro film The Mask of Zorro and Christian Bale’s films.

_________________________________________

Interesting point about which properties derive from magic and which derive from the laboratory/SF. I remember that I tried to determine whether the “classic monsters” came from the laboratory or from magic. For those wondering:

Frankenstein’s Monster: assembled in a lab

Invisible Man: result of lab work

Mr. Hyde: result of lab work

King Kong: derived from The Lost World

The Phantom of the Opera: does not have paranormal powers

Fantomas: see above

Captain Nemo/Prince Dakkar: just relies on a submarine

I remain uncertain as to where to slot Doctor Mabuse.

Ayesha and Dracula explicitly have sorcerous aptitude

So, looking at the comic book heroes, where they fall on the laboratory or magic side:

Superman: an extraterrestrial

The Hulk: military research accident

The Flash: laboratory accident

The X-Men: mutants, sometimes called “the Children of the Atom”

Iron Man: relies on laboratory work

Captain America: laboratory work

Daredevil: gained his powers from toxic waste, in the fact the same toxic waste that empowered:

Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles: resulte from the same accident that instigated Daredevil

You will notice that in the 1950’s and 1960’s, some of the revamps of “Golden Age” properties went for more outer space elements (e.g. Hawkman the Egyptian prince reincarnated replaced by a member of an extraterrestrial police force, Green Lantern with a magic ring replaced with a member of an extraterrestrial police force). (The revised Green Lantern resembles the Lensmen.)

On the other hand, Shazam, of course, has magic powers, and Wonder Woman relies on Amazon magic. Aquaman and Namor have connections to Atlantis, making the somewhat magic related.

Another nice one, Matthew. I have often pondered what the comics medium/super-hero genre could teach us about about successful mash-ups for prose. I really want to turn out work that defies genre expectation while embracing it, and do so for multiple genres within a single story.

I think you’re correct that there is a desire to make Thor “grounded” for the Avengers movie. I eagerly await that movie but also am a little sad that if you are right, what was lost in a Thor what-might-have-been franchise because of it.