Galaxy, December 1965: A Retro-Review

I picked up a few magazines at an antique store near Columbia, MO, last week, including three consecutive issues — of different magazines — from the end of 1965/beginning of 1966: the December 1965 Galaxy, the January 1966 F&SF (reviewed here), and the February 1966 Analog. The first one I got to was the Galaxy.

I picked up a few magazines at an antique store near Columbia, MO, last week, including three consecutive issues — of different magazines — from the end of 1965/beginning of 1966: the December 1965 Galaxy, the January 1966 F&SF (reviewed here), and the February 1966 Analog. The first one I got to was the Galaxy.

This is from more or less the center of Frederik Pohl’s editorial tenure. Galaxy in this period was bimonthly, with two sister magazines — Worlds of Tomorrow, also bimonthly, and Worlds of If, which was monthly. (I admit I had not known that — I thought it was also bimonthly, and I’m surprised that Galaxy, the “senior” magazine, was not the monthly one.) Galaxy was generously sized, at 196 pages (including covers), with about as much fiction as Analog and Asimov’s feature these days. By contrast Worlds of Tomorrow had 164 pages per issue, and If only 132. The latter two were 50 cents, but Galaxy was 60 cents. (I find this mixture of format, frequency, and pricing in three magazines from the same stable rather intriguing.)

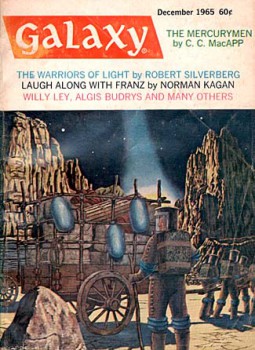

The cover of the December 1965 Galaxy is by Pederson, illustrating “The Mercurymen”, by C. C. MacApp. (Galaxy typically only credited last names for artists — apparently this particular artist was named John Pederson, Jr. — I’m not very familiar with his work, and not too impressed with this particular example!) Interiors were by Gray Morrow, Giunta, Jack Gaughan, and Wood. (The artists whose first names I know are, not surprisingly perhaps, the better ones, though I am told that John Giunta and Wally Wood were well known for work in comics.) There are a fair number of ads — more than often in SF magazines — though somewhat low rent ones: Rosicruans, hypnotism, the Puzzle Lovers Club, the Book Find Club, book plates (from Galaxy), and the Duraclean Company.

The features include an editorial by Pohl, “To The Stars”, which talks about a guy named Dr. Robert Enzmann, who was claiming that spaceships capable of a trip to Pluto in a few weeks would be possible in about 20 years. Such overblown claims (overblown perhaps more due to economics and social reality than technical plausibility) were very common in the SF magazines of the time.

The features include an editorial by Pohl, “To The Stars”, which talks about a guy named Dr. Robert Enzmann, who was claiming that spaceships capable of a trip to Pluto in a few weeks would be possible in about 20 years. Such overblown claims (overblown perhaps more due to economics and social reality than technical plausibility) were very common in the SF magazines of the time.

But note that that 20 year period expired pretty much exactly in January 1986 — so instead of a trip to Pluto we got Challenger. Sigh. (One nice detail is that Enzmann had been a Boy Scout in a troop led by Hal Clement.)

Willy Ley’s “For Your Information” is about “That Helpful Aromatick Herbe”: i.e., tobacco. The Forecast looks forward to short novels by Cordwainer Smith (“Under Old Earth”), and Jack Vance (“The Last Castle”), the linking factor being that both writers were world travelers.

Finally, there’s Algis Budrys’s Galaxy Bookshelf. Budrys talks first of the problems a writer has being properly read — essentially, the notion that each reader reads a different book. (Compounded, Budrys notes, by simple things like misreading words (one example: Rogue Moon being called Rouge Moon). Also compounded by editors’ changes to writers’ words, etc. etc.)

Then the reviews. He gives Lester Del Rey’s collection Mortals and Monsters a rave review — probably worth thinking about, given that that book is essentially forgotten, and that Del Rey’s reputation as a writer (not editor) is seriously in eclipse.

Then he goes on to Robert Silverberg’s collection To Worlds Beyond. And Budrys is quite vicious about the collection.

Then he goes on to Robert Silverberg’s collection To Worlds Beyond. And Budrys is quite vicious about the collection.

What must be noted (Budrys, to be fair, does note it) is that the stories date to 1956-1959. Since that time Silverberg had largely left the field, and was just then returning to very active SF writing.

One might also note Judith Merril’s review, in the January 1966 F&SF that I mention above, of Brunner’s The Whole Man, in which she lauds that fine book, and says of Brunner “he might have become a … Silverberg.”

But Brunner did! — If you mean by “a Silverberg” a writer who devoted himself to the prolific production of competent but usually not exceptional work.*

And then Brunner decided to write more serious work, beginning, in essence, with The Whole Man. What Merril missed, and Budrys too, is that Robert Silverberg was going through a very similar transformation.

To be fair, the best of Silverberg’s magnificent “Middle Period” work was yet to come. But a few stories suggestive of his improvement were already out — I’d suggest “To See the Invisible Man” and “The Pain Peddlers” for a couple.

Budrys closes his column with praise for an unusual-seeming mainstream-marketed book I’ve never heard of, The Cook by Harry Kressing.

(*And check out Silverberg’s heartfelt appreciation for Brunner, delivered at the 1995 Glasgow Worldcon where Brunner, the Guest of Honor, had a stroke and died suddenly, and reprinted in Locus. Silverberg said, after pointing out some of the ways their two careers were “entwined”: “we pointed out to each other that he was the British Robert Silverberg and I the American John Brunner.”)

(*And check out Silverberg’s heartfelt appreciation for Brunner, delivered at the 1995 Glasgow Worldcon where Brunner, the Guest of Honor, had a stroke and died suddenly, and reprinted in Locus. Silverberg said, after pointing out some of the ways their two careers were “entwined”: “we pointed out to each other that he was the British Robert Silverberg and I the American John Brunner.”)

(I should note that I read early Silverberg and early Brunner with considerable enjoyment — but I certainly see that they both took a quantum jump in quality and seriousness in the mid-60s. Though I would say that I like early Brunner more — and later Silverberg more.)

Now to the stories.

There are three novelettes, a very famous short story, a serial section, and a “Non-Fact Article” that I choose to list with the fiction.

Given the discussion above, it’s interesting to note that fiction in this issue comes from Robert Silverberg and John Brunner — not to mention Harlan Ellison, whose career also began in the mid ’50s with a spate of competent but minor work, and who also was just at this time beginning to produce the work that would make him famous — indeed, this story is one of his most famous.

So:

- “The Mercurymen”, by C. C. MacApp (17500 words)

- “Laugh Along With Franz”, by Norman Kagan (8800 words)

- “The Warriors of Light”, by Robert Silverberg (13200 words)

- “‘Repent, Harlequin!’, said the Ticktockman”, by Harlan Ellison (4200 words)

- “Galactic Consumer Reports No. 1 — Inexpensive Time Machines”, by John Brunner (2800 words)

- “The Age of the Pussyfoot, part 2”, by Frederik Pohl (13500 words)

C. C. MacApp was, as far as short fiction goes, almost purely a one editor writer, that editor being of course Pohl. His first story appeared in If in 1960, and his last in Galaxy in 1971 (after Ejler Jakobsson took over). He did publish five stories in Cele Goldsmith’s Amazing and Fantastic, and one in Analog under his real name, Carroll M. Capps. So, 34 of his 41 published short stories went to Pohl. But he died in 1971, only 54 years old — so he’d hardly had a need to look to any editor but Pohl, who after all snapped up just about everything he wrote, seems like. MacApp also published seven novels, for paperback houses like Paperback Library, Avon, Lancer, and Dell.

The story of Larry Niven’s first sale, “The Coldest Place”, is well known — he set the story on a Mercury which was in perfectly synchronous rotation with its orbit, such that it had a day side and a night side. When Fred Pohl bought it for If, that was the state of scientific knowledge, but by the time it was published in the December 1964 issue, it was known that Mercury is instead in a 3:2 synchronous rotation, so that the whole planet is exposed to the Sun for extended periods. Well, “The Mercurymen” was published exactly one year after “The Coldest Place”, and it STILL uses the idea of a Mercury with a day side and a night side. It’s fairly routine SF adventure, not bad of its type, about a society inhabiting huge trees apparently genetically engineered to straddle the day and night sides, such that they are habitable in the “twilight”. Periodically, a group of people leaves one tree and heads to a new tree to colonize it. This story concerns one young man who is tapped to lead such a group, but runs into trouble with a jealous older man, trouble exacerbated by the young man’s ties with a too young girl who sneaked onto the exhibition. Things change when they encounter a different group — “traders”, and the young man must choose a future for himself.

“Laugh Along With Franz” is a politically oriented story about a college student and computer programmer in a future mostly run by AIs. The title refers to Franz Kafka, because a vote for “No Preference” is allowed in this future — an “alienated vote” — meant as a reference to people as alienated from society as Kafka’s characters. Our hero is involved with a beautiful woman, and he happens to have a fairly rare job, but he too is alienated.

“Laugh Along With Franz” is a politically oriented story about a college student and computer programmer in a future mostly run by AIs. The title refers to Franz Kafka, because a vote for “No Preference” is allowed in this future — an “alienated vote” — meant as a reference to people as alienated from society as Kafka’s characters. Our hero is involved with a beautiful woman, and he happens to have a fairly rare job, but he too is alienated.

The story is long and rambling, with some intelligent ideas (some rather prescient ones), and with certain points of contact with such later stories as those in Thomas Disch’s 334, but I found it boring — plausible, in many ways, with a believable main character, and quite ambitious, but just not interesting.

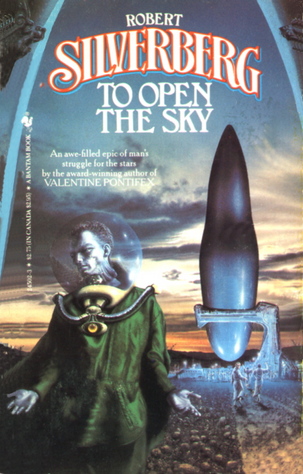

Silverberg’s “The Warriors of Light” is about an ambitious acolyte in a future religious organization, the Brotherhood, built on scientific principles, and devoted to achieving life extension for humanity. His ambition trips him up, and promises to stunt his advancement, so he becomes vulnerable to recruitment by a heretical splinter group, which arranges for his transfer to the hub of the Brotherhood’s research program, in exchange for his agreement to spy for the splinter group. The whole working out is rather cynical, in a believable way.

The story seemed to call for both predecessors and sequels, and it turns out that indeed it is the second of five stories which were knitted together into one of the first of Silverberg’s middle period novels, To Open the Sky. (I haven’t read the novel.) This is fine work, though not as intense nor as absorbing as much of the great work that was coming from Silverberg in the succeeding years.

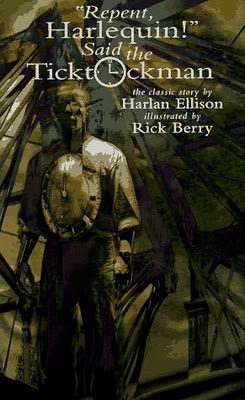

Harlan Ellison’s “‘Repent, Harlequin!’, said the Ticktockman” is a very famous story, winner of the first Nebula for Best Short Story as well as a Hugo.

I really liked it on first reading, but I found it less impressive rereading it now. It’s about a man in a highly regimented future throwing wrenches into the system, as I’m sure everyone knows. Lots of pizzazz, lots of energy, verbal imagination, but at this remove not quite convincing to me.

I really liked it on first reading, but I found it less impressive rereading it now. It’s about a man in a highly regimented future throwing wrenches into the system, as I’m sure everyone knows. Lots of pizzazz, lots of energy, verbal imagination, but at this remove not quite convincing to me.

Still, a strong and historically important story. Looking through lists of stories from 1965, it probably is the best short story on the nomination list (though an argument could be made for Lafferty’s “Slow Tuesday Night”), but since the Hugo was for “short fiction” (including novelettes and novellas), I’d have gone for Roger Zelazny’s “The Doors of His Face, the Lamps of His Mouth” (which did win the Nebula for Best Novelette).

And the actual best short story that year, in my opinion, was David Masson’s “Traveller’s Rest”, but in those days a story from the UK magazine New Worlds would have a tough time getting a Hugo in a US convention, just because too few voters saw it.

The Brunner contibution, labelled a “Non Fact Article”, is fairly amusing, in the form of a Consumer Reports survey of time machines.

And the Pohl serial is of a novel of his I haven’t read, and I skipped this “middle part”.

Over several years in the early 2000s, and thousands of dollars, I used primarily eBay to buy up complete collections of F&SF, Galaxy, Analog, Asimov’s, and possibly some others I’m forgetting. Obviously I haven’t had time to read, well, any of them: That’s my retirement project! 😉 I bought quite a few of them from Darrell Schweitzer himself.

But while I haven’t had time to read them, I did like going through and reading the book and movie reviews. Quite interesting.

And yes, the issues with Philip K. Dick stories usually cost the most–some of them even more than the very first issue of F&SF.

[…] Here’s the second of three consecutive months of SF magazines I recently bought, each a different specimen of the canonical “Big Three” of that time. The first, the December 1965 issues of Galaxy, is here. […]

[…] canonical “Big Three” of that time. The first, the December 1965 issue of Galaxy, is here, and the January 1966 issues of The Magazine of Fantasy & Science Fiction is […]

[…] digest magazines from the mid-20th Century. The first three were the February 1966 Analog, the December 1965 Galaxy, and the January 1966 issue of The Magazine of Fantasy & Science […]

[…] You can find retro-reviews of the May 1952 issue of Galaxy Science Fiction here, and the December 1965 issue here. […]

[…] digest magazines from the mid-20th Century. The first four were the February 1966 Analog, the December 1965 Galaxy, the January 1966 issue of The Magazine of Fantasy & Science Fiction, and If, October […]